Lili Bita, Cultural Affairs Correspondent

Special to the Hellenic News of America

My Dear Readers and Friends,

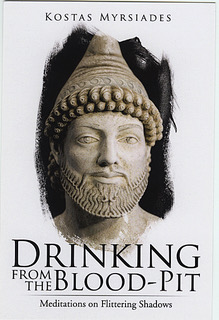

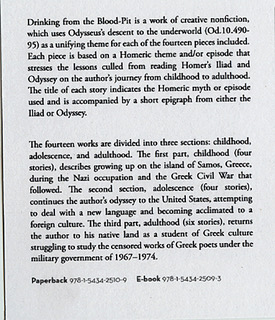

Today I would like to present to you a remarkable new book by the eminent scholar, Dr. Kostas Myrsiades, Professor of Comparative Literature Emeritus at West Chester University and winner of the Hellenic Gold Medal for literary translation from the Greek government. Drinking from the Blood Pit, a reference to the ancient ceremony that invokes the underworld, combines key passages and events from Homer’s Odyssey with the author’s own autobiographical experience to suggest how the most ancient of all Greek journeys is also a very modern one. The voyage of Odysseus, from his departure from Ithaca to his return to his wife, Penelope, took Homer’s hero twenty years. Dr. Myrsiades’ own journey, a far longer one, has taken him a good deal further, and through a century every bit as perilous as the Homeric Aegean.

To go back so far in time and return from the lands of the dead, one must first make an offering. Dr. Myrsiades’ follows the ancient prescription:

“Dig a pit about a cubit in each direction, and pour it full of drink offerings for all the dead, first honey mixed with milk, then a second pouring of sweet wine, and then a third, water, and over all this sprinkle white barley.”

With this libation, we, too, may enter this moving and remarkable book.

The book is divided in three sections (“Childhood,” “Adolescence,” “Adulthood,”) with a total of fourteen chapters, each keyed to passages in The Odyssey. Myrisades prefaces these sections with another modern account of Homer’s tale, Constantine Cavafy’s famous poem, “Ithaka,” in Myrsiades own translation:

When you start out from Ithaka,

pray the road be long,

full of adventures, full of insights,

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

wrathful Poseidon, you need not fear,

for they will never cross your path,

if your thoughts remain lofty, if a rare

emotion takes hold of your soul and body.

You will not encounter wild Poseidon,

the Laistrygonians and the Cyclops,

if you do not carry them within your soul,

if your soul does not raise them before you.

Hope that the road be long,

and many the summer mornings

when with pleasure, with joy

you sail into harbors for the first time,

to stop at Phoenician markets

to acquire fine merchandise,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfumes of every type,

as many of these perfumes as you can gather;

and sail to many Egyptian cities,

to hear and learn from those with knowledge.

Always keep Ithaka in mind.

Arriving is your goal.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better for it to last many years;

to arrive on the island old,

wealthy with all you gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to give your riches,

Ithaka gave you the beautiful journey.

Without her you would never have set out.

She has nothing more to give.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka has not deceived you.

Wise as you will have become, full of experience,

you will have understood what Ithakas mean.

Myrisades segues from this directly into an account of his birth island, Samos, and his own earliest childhood on it, ending first with the devastation wrought by the Nazis and then by the civil war. There is a powerful, lyrical evocation of his first experiences, and then, at the end, a brief account of his emigration to the United States in 1947: as Myrsiades puts it, “Like Odysseus, I was not to return to my Ithaka until 20 years later, a stranger to all but my parents . . .”

In “Childhood,” Myrsiades recalls evokes episodes from his early years that relate to Homer’s poem. In “Eating the Cyclops’ Eye,” the connection is amusing, as Myrsiades recalls the single fried egg he ate for lunch as the giant’s single eye. “The Elysian Fields” connects the ancient sense of the living and the dead as interconnected with the care of the dead among his own people. “The Scar” relates Odysseus’ youthful scarring by a boar to his own scorching by the ignition of unspent bullets left over during the civil war.

In “Adolescence,” Achilles and Kalypso accompany Myrsiades as he adjusts to life in America and comes of age. “Adulthood” brings him back to Greece during the years of the Junta, where he makes the acquaintance of the exiled poet Yannis Ritsos, a fellow Samian whose work he would splendidly translate, with Kimon Friar, in Scripture of the Blind, and other victims of the dictatorship whose torture would equal anything out of Homer. The climax of the book relates the fall of the Junta, and, as a coda, Myrsiades’ meeting with the legendary Manolis Glezos, for him, as for many others, the living embodiment of Homeric aristeia.

One of the most interesting figures we meet is Hristos Haridimos, a master of the performance folk art of Karagiozis to which Myrisiades has devoted much of his scholarly career and on which he is an internationally recognized expert. It is one of the many brilliant thumbnail sketches that stand out along Myrsiades’ personal journey.