by Ambassador Andrew Jacovides

Harvard Club, New York, 5 October 2017

Excellencies, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Friends,

I feel truly privileged to be addressing you on a subject which has been of great importance to me for the past several decades. I am grateful to the Foreign Policy Association and its President, my friend Noel Lateef, and to Mr. Joseph Ficalora, the President of the New York Community Bank Corp., for entrusting me with the pleasant task of giving this year’s Spiros Voutsinas lecture.

We all know the distinguished place the Foreign Policy Association occupies in the field of foreign affairs for nearly one hundred years. It also so happens that Spiros Voutsinas was the one who selected me to serve, together with other distinguished friends, some of whom are present here, on the Advisory Board of the Atlantic Bank, under the overall direction of the highly respected Joseph Ficalora, CEO, COO of NYCB. Spiros, an immigrant from Greece, achieved through his ability and hard work, the American Dream and was, most recently, the President of the Atlantic Bank in the service of the Greek American, but also the broader American community, a task ably carried on by his successor Nancy Papaioannou. I recall being invited by Spiros to the first event I attended of the Foreign Policy Association and I am honored to deliver this lecture dedicated to his memory.

If I may add, I am especially pleased to be speaking at the Harvard Club, where I have been a member for the past four decades and where I lectured in the past as the Ambassador, then, to the United States, at the suggestion of Dr. John Brademas, the then President of NYU. I remember that on that occasion, John being late to arrive at the club, humorously said “allow me to introduce the late Dr. Brademas”. Sadly, he and Spiros Voutsinas are both “late” now!

Before we go any further, let me make clear that here I speak not as a government official but as a private individual, Cypriot citizen and voter, passionately concerned over the future of my country which I served for many years, beginning at its independence in 1960. This has the advantage that I will tell you what I really think, as distinct from what the official line is. I also regret to inform you that, perhaps as a generational thing, I will not be using power points or even the teleprompter in delivering this lecture. Once somebody said that he thought I was a “warm speaker” and I liked that, until it dawned on me that by warm was meant not so hot! I have the feeling that Spiros, had he been here, would have preferred it this way.

Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Friends,

Our topic today “The Role of the UN in Conflict Resolution” would of course be too broad for a lecture if it were not limited to “The Case of Cyprus”.

The on conflict resolution Articles of the UN Charter are Article 2(3), which reads:

“All Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international securities, and justice, are not endangered”, while Article 33 reads:

“ 1. The parties to any dispute, the continuance of which is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security, shall, first of all, seek a solution by negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice”.

These basic provisions of the UN Charter should be read in the context of two other basic provisions; Article 2(1) states that

“The Organization is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members”.

This is a principle that mostly small States invoke and cherish but you may recall that this is one on which President Trump placed great emphasis at his General Assembly presentation at the General Debate last month.

Article 2(4) is also a key relevant provision. It states that

“All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations”.

Under this basic Charter provision, which is a peremptory norm of international law, the prohibition against the use or threat of force in international relations is absolute and the two exceptions should be interpreted narrowly. The eminent Professor, Sir Humphrey Waldock, cogently stated that “The final result is that Article 2(4) prohibits entirely any threat or use of force, between independent states, except in individual or collective self defense under Article 51 or in execution of collective measures under the Charter, for maintaining or restoring peace. Armed reprisals to obtain satisfaction for an injury or armed intervention as an instrument of national policy otherwise than for self defense, is illegal under the Charter”. This may sound too idealistic but it is the law in force.

This provision is particularly relevant in interpreting Article IV of the 1960 Cyprus Treaty of Guarantee and is quoted in the key Security Council Resolution 186 (1964), as we shall see later.

Dear Friends,

It has long been my conviction, that if the rules of international law had been applied, the problem we have been confronted with in Cyprus, would not have arisen. And, if they are applied now, the problem would be solved to the satisfaction of all Cypriots and for peace in the region. Of course other factors, constitutional, political, economic, psychological, historical, are also relevant, but international law in my view is a major factor.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Bearing in mind the basic Charter provisions cited above, the case of Cyprus furnishes an excellent illustration of the way UN conflict resolution has been applied in a variety of ways over the years.

The General Assembly and the Security Council played a major role through many resolutions; the Secretary-General, as early as 1964, exercised his good offices and continues to do so; there has been mediation through SC Resolution 186 in 1964 and also arbitration by the UN Special Representative through the February 2004 decision. There has been, as yet, no resort to judicial settlement but, as I shall explain later, it was a distinct possibility to have resort to the International Court of Justice for an Advisory Opinion on the key question of Article IV of the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee (and, of course, there have been many relevant judicial decisions by the European Court of Human Rights such as the Loizidou v. Turkey case and relevant cases before British and American courts, the Kanakaria Mosaics case, being a prime example). I am convinced that, had there been a recourse to the International Court of Justice, Cyprus would have had an ironclad case.

But before we go into this, let me remind you by way of background, that Cyprus, an island in the eastern Mediterranean, located at the crossroads

of three continents – Europe, Asia, Africa – with a land area of 3,572 square miles, and a population of about one million, (of whom 80% are Greek Cypriots, 18% Turkish Cypriots and the remainder other small minorities of Maronites, Armenians and Latins), became independent on August 16, 1960, after 82 years of British colonial rule.

During our long, proud and turbulent history, stretching back to 6,000 years BC- as part of the Hellenic world of antiquity referred to in Homer as the birth-place of Aphrodite, -the goddess of love and beauty-, conquerors came and went leaving behind them some traces and monuments to mark their passing and adding to our already rich cultural heritage, but never altering the basic ethnological character or unity of the island. Yet now, in the era of the United Nations, the spectre of partition looms large and real.

The Turkish Cypriots appeared in Cyprus after the island became, as was the case with all other territories in the region, part of the Ottoman Empire, following its conquest from the Venetians in 1571. They were interspersed throughout the island, living peacefully with the majority Greek Cypriot population. It was after the Turkish invasion and occupation in 1974 – to which I shall revert – that, in a blatant manifestation of ethnic cleansing, the Turkish occupation forces forcibly expelled from their ancestral homes more than 1/3 of the Greek Cypriots, while our Turkish Cypriot compatriots were compelled by Turkey to relocate from the areas controlled by the Cyprus Government, in which they used to reside peacefully, to the areas occupied by Turkey. Through the continuous presence of over 40 thousand heavily armed Turkish troops and through the importation of many tens of thousands of implanted Anatolian settlers in a deliberate effort to alter the age-long demographic character of the island, Turkey established an illegal entity (declared to be legally invalid by Security Council resolutions 541 and 550) which is under its absolute political, economic, cultural and religious control and dominance, and which is steadily more and more Islamized.

So much by way of background. Reverting to the main theme of today’s lecture, let me recall that the Cyprus conflict went through several phases, in all of which the United Nations played a key role.

In the middle and late 1950s, there was the pre-independence struggle of the Greek Cypriot majority, with the support of Greece, for self-determination and enosis / union with Greece. This was countered by the claim of the Turkish Cypriot minority, with the support of Turkey, for taksim / partition, with the encouragement of the colonial power, applying the principle of divide and rule. Following a number of inconclusive recourses by Greece to the General Assembly, the idea was suggested by, among others, Krishna Menon of India, that the solution should be to have neither enosis nor taksim, but independence. This idea was accepted in principle by the Greek Cypriot leader Archbishop Makarios as a compromise and the Greek and Turkish Governments reached an understanding in Zurich in February 1959, to which Britain was added in London a week later. The Zurich-London Agreements constituted the UN inspired compromise, upon which the Cyprus independence was based. The package included the Treaty of Establishment, the Treaty of Alliance and the Treaty of Guarantee, whereby the three powers, Turkey, Greece and the United Kingdom, guaranteed an inflexible, unique constitution of the new Republic of Cyprus. Parallel to this the British government secured two substantial military sovereign bases (thus resolving the debate whether Britain wanted “Cyprus as a base, or a base in Cyprus”).

In the circumstances prevailing in August 1960 many had misgivings about the future of the new Republic, and doubted whether its creation was a cause for celebration. In light of the turbulent and eventful experiences since that time, it can be stated with conviction that statehood and independence, even subject to the limitations imposed by the Zurich-London Agreements, as evolved from early 1964 on, have been an asset to be treasured and defended against the constant attempts to diminish and destroy it.

When Cyprus, as an independent State, was unanimously admitted to the United Nations on 20 September 1960 (I had the honor to be a member of the delegation, under the venerable Ambassador Zenon Rossides) it started with a clean slate. It was hoped that the traumatic experiences of the years immediately preceding would be forgotten and that despite its small size in population, Cyprus would be able to play a constructive role in international affairs by taking positions on issues before the Organization on the merits of each issue, in relation to the principles of the Charter (a position authoritatively articulated by President Makarios in his address to the General Assembly in 1962 – which I helped draft). The international climate at the time was conducive to this end. It was the time for the emergence from colonial rule of many new States, several of them from Africa, which upon independence joined the United Nations, thus transforming its composition and voting patterns. It was the time when the concept of non-alignment was first elaborated upon in the 1961 Belgrade Conference, where President Makarios participated and became a sizable force in world affairs. It was the time when, under President Kennedy and Chairman Kruschev, respectively, the United States and the Soviet Union were eagerly competing for influence among the non-aligned and newly independent States.

In short, the circumstances were propitious, and the delegation of Cyprus, through its active participation on issues before the various UN Organs, effectively played a role considerably exceeding that which would be expected if one only took into account its size and population.

It should be remembered that the period of September 1960 to the end of 1963, was the time, in fact the only time, when Cyprus was not laboring under a problem of its own. During this formative period, Cyprus made the United Nations and the principles of its Charter central to its foreign policy, and this had a significant and direct effect upon subsequent developments.

In December 1963, when following intercommunal clashes, after the rejection of the 13 Points Proposal put forward by President Makarios in order to overcome the constitutional deadlock, the Republic of Cyprus was confronted by serious threats and acts of intervention by Turkey, it was only natural that it should turn for protection to the UN and seek the application to its case also, of the Charter principles for the application of which it had struggled in the case of others. Correspondingly, the Organization through its political organs, notably the Security Council and the General Assembly, as well as the Secretariat, responded positively to this appeal.

The Cyprus problem was formally placed before the United Nations for the first time since the pre-independence events, through a letter of the Permanent Representative of Cyprus, who, on behalf of his government, lodged a complaint to the Security Council, charging Turkey with acts of aggression and intervention, in violation of Turkey’s obligations under the Charter. This letter (S/5488 dated 26 December 1963 – which I happened to have drafted for Ambassador Rossides’s signature) was inscribed on the Council’s agenda and, as subsequently supplemented, has been the basis of the Cyprus item in the Security Council from then on. The Security Council ignored the objection of the then Turkish Cypriot Vice President Kutchuk, who alleged that he had the right of veto under the Cyprus Constitution, on the ground that this letter emanated from the legitimate representative of Cyprus who acted on behalf of the duly recognized President of the Republic.

After the failure of the London Conference in January 1964 (a six power regional conference with the participation of the three Guarantor Powers, the Government of the Republic of Cyprus and the two Cypriot communities) and certain NATO initiatives, the Cyprus question was referred back to the Security Council and was extensively considered in meetings during February and March 1964. After protracted deliberations, it adopted on 4 March 1964 the landmark resolution 186 (1964) which has since been repeatedly reaffirmed and which provided the basic framework for the Security Council’s action. Resolution 186 (1964) was based on the premise that, under Article 2(4) of the Charter, all Members of the United Nations shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

In its three main elements, Resolution 186 provided (i) that the above principle should be respected with regard to Cyprus; (ii) that a United Nations Peace-Keeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) be set up, with the consent of the Government of Cyprus, and laid down its mandate and modalities; and (iii) that a United Nations Mediator be appointed for the purpose of promoting a peaceful solution and an agreed settlement of the problem confronting Cyprus in accordance with the Charter. While the Council took no clear position as to the validity or invalidity of the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee, by calling for respect of the principle cited in Article 2 (4) above, it indirectly vindicated the Cyprus Government’s claim that the Treaty conferred no right to use military force against Cyprus in violation of this peremptory norm (jus cogens) of international law which prevails over any treaty which is in conflict with it, as well as under Article 103 of the Charter.

Let us now consider how this Resolution was implemented: In so far as element (i) was concerned, Turkey continued the threat and use of force against Cyprus and this necessitated additional Security Council emergency sessions, such as that in August 1964. Regarding element (ii), UNFICYP was set up and it is generally acknowledged that it has been discharging its functions, as set out in the Resolution and interpreted from time to time in the light of factual developments by the Secretary-General, in a commendable manner. While it was set up originally for three months only, it has proven necessary for the Security Council, on the recommendation of the Secretary-General, to renew its mandate time and again in six-monthly intervals as its presence is still considered indispensable. As for element (iii) in Resolution 186, the Secretary-General designated as United Nations Mediator, originally Mr. Tuomioja (Finland) and after his sudden death in August 1964, Dr. Galo Plaza (Ecuador). Dr. Plaza’s Report, which he submitted to the Secretary-General on 26 March 1965, was a closely reasoned, judicious and constructive document which was fully consistent with his mandate under para.7 of the Resolution 186 and, in the opinion of all impartial observers, both at the time and in retrospect, could have formed the basis of a fair, just and viable solution to the Cyprus problem.

In some of his observations, Dr. Plaza proved prophetic when one looks at his Report now in the light of the intervening developments and with the benefit of hindsight. Thus, referring to the Turkish proposal for federation, he wrote “it seems to require a compulsory movement of the people concerned – many thousands on both sides – contrary to all enlightened principles of the present time, including those set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”. He also wrote: “In fact, the arguments for the geographical separation of the two communities under a federal system of government have not convinced me that lit would not inevitably lead to partition;” and, further, that the physical division of the minority from the majority should be “considered a desperate step in the wrong direction”. Despite the fact that the Secretary-General supported Dr. Plaza’s interpretation of his mandate, his Report was flatly rejected by Turkey on the spurious ground that he exceeded his mandate, and this caused the subsequent resignation of Galo Plaza. Even though certain quasi-meditational functions were conferred by the Secretary-General upon his Special Representative in Cyprus in 1966 and the latter exercised his good offices in this regard, regrettably the United Nations mediation system under para.7 of Resolution 186 has remained dormant ever since that time.

Two comments are called for in this regard; The first is that if the Security Council strongly supported the Mediator appointed under its own resolution, and the solution was reached upon his recommendations, accepted by Cyprus, the problem would have been solved fairly and lastingly as of that time and this would have spared Cyprus the disastrous effects of the coup and the invasion of 1974. It would also have made possible as early as 1965 the discontinuation of UNFICYP, as was the original design. This should be remembered, especially now, that the need for an exit policy for peacekeeping operations, is given emphasis by the Security Council.

The second observation is that if the suggestion of Secretary-General U-Thant to refer the question of the legality of Article IV of the Treaty of Guarantee and, in particular, whether it conferred the right of forcible intervention (an issue which was raised by the Foreign Minister of Cyprus in the Council at its 1098 meeting and to which opposite responses were given by the Turkish and Greek representatives, with that of the United Kingdom giving an ambiguous reply) to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion. If this had been done and the ICJ clarified the legal issue (as successive Presidents of the ICJ, Jennings, Schwebel, and Shi advocated as a means of helping solve the political disputes), we would not still have to face different interpretations which partly caused the failure of the latest round of talks in Switzerland. It so happens that, at two gathering of prominent international lawyers convened by Cyprus’s Attorney-General in Geneva in 1999 an in The Hague in 2000, -where I participated- this, among other issues, was unanimously clarified on the correct lines, but an ICJ Advisory Opinion would of course have carried more weight. The ICJ indirectly dealt with the Cyprus situation in two reassuring paragraphs, 81 and 84, of the recent Kosovo Advisory Opinion. But this was done to make a distinction between Cyprus and Kosovo and thus was not directly to the point.

It is sometimes overlooked that during this period, the General Assembly was also seized of the Cyprus question at the initiative of the Cyprus Government. In 1965 it adopted GA resolution 2077 (XX) which was fully debated in the First Political Committee and amounted to a full vindication of its position for the full sovereignty, complete independence, unity, and territorial integrity of Cyprus. Positive reference was made to the Report of the UN Mediator and also to the Declaration of Intent and Memorandum of the Cyprus Government, whereby it committed itself to the full application of human rights to all citizens of Cyprus, irrespective of race of religion and in which the Government offered to adopt any appropriate machinery that the Secretary-General on the advise of the Human Rights Commission might recommend in order to ensure the practical observance of these rights. This resolution was also brusquely rejected by Turkey.

During the period of 1968-1974 internal talks were carried out on constitutional issues within the framework of the Good Offices of the Secretary-General and on the basis of a unitary, independent and sovereign State of Cyprus. Even though these talks made progress, they did not produce a breakthrough until they were brought to an abrupt end by the events of the Summer of 1974.

In July 1974 the criminal coup d’ etat by the junta, which at that time was ruling Greece and the Turkish invasion which followed using it as a pretext, with the ethnic cleansing and continuing occupation which followed, created a drastically different situation.

Time does not allow furnishing the details of the UN response. UNFICYP responded by adjusting its mandate to the new situation, and continued its operation as best as could be done under the circumstances by interposing between the Turkish forces of occupation and the Cyprus National Guard.

The Security Council responded by passing a series of resolutions, beginning with resolution 353 (1974) adopted on 20 July 1974,the very day when the Turkish invasion began, in which, inter alia, called for a cease fire and demanded an immediate end to foreign military intervention – which were ignored by Turkey. By December of the same year, the Security Council, in addition to renewing UNFICYP’s mandate, unanimously adopted another resolution 365 (1974) by which it endorsed General Assembly resolution 3212 (which was earlier unanimously adopted by the General Assembly) thus vesting its provisions with the authority of the Security Council. In March 1975 the Security Council adopted resolution 367 (1975) by which, inter alia, requested the Secretary-General to undertake a new mission of Good Offices towards comprehensive negotiations.

The General Assembly also held extensive debates in 1974 and subsequent years and adopted several landmark resolutions such as 3212 (1974) unanimously, and 3395 (1975) by 117 votes in favor, with only Turkey voting against.

Major declarations pledging support for the Government of Cyprus and calling for the withdrawal of the foreign troops and the return of the refugees were also adopted by successive Non-Aligned and Commonwealth conferences (in Havana, Lima and Kingston, respectively) – in all of which I happen to have participated. These were diplomatic successes but of no practical effect.

It is sometimes said that in UN Resolutions the wording is intentionally vague and Turkey is not pointed out by name. There is some element of truth in this but it is not correct where all factors are considered.

For instance, General Assembly Resolution 37/253 (1983) of May 1983, (which, inter alia, “welcomes the proposal for the total demilitarization made by the President of Cyprus (para.4) the General Assembly “Demands the immediate withdrawal of all occupation forces from the Republic of Cyprus “ (para.8). The same resolution deplores “the fact that part of the territory of the Republic of Cyprus is still occupied by foreign forces” and “all unilateral actions to change the demographic structure of Cyprus” and reaffirms “the principle of inadmissibility of occupation and acquisition of territory by force”.

Likewise, in Security Council Resolutions 541 (1983) and 550 (1984), the Security Council takes categorical positions on the purported unilateral declaration of independence by the so-called “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus”, describes the declaration “legally invalid and calls for its withdrawal”. It also called upon all states “not to recognize any Cypriot state other than the Republic of Cyprus” and condemned “all secessionist actions, including the purported exchange of Ambassadors between Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot leadership, declares them illegal and invalid, and calls for their immediate withdrawal”. To this date, no state, other than Turkey recognizes the so-called “TRNC”.

Returning to our main theme, the role of the UN in conflict resolution in Cyprus, many negotiations have taken place, under successive Secretary-Generals (Waldheim, Perez de Cuellar, Boutros Ghali, Kofi Annan, Ban Ki-moon and Antonio Guterrez) the last one being in Crans Montana, Switzerland, in July this year. Progress has been made but they have not produced a breakthrough.

The terms of reference on which these negotiations are conducted are set out in Security Council Resolution 939 (1994) and these are the agreed basis on which the talks have been conducted by successive Special Representatives of the Secretary-General (the most recent one being Espen Barth Eide of Norway):

“ A Cyprus settlement must be based on a State of Cyprus with a single sovereignty and international personality and a single citizenship, with its independence and territorial integrity safeguarded, and comprising two politically equal communities as described in the relevant Security Council resolutions in a bi-communal and bi-zonal federation, and that such a settlement must exclude union in whole or in part with any other country or any form of partition or secession”.

This has been the basis upon which the UN has been endeavoring to resolve the Cyprus conflict and remains so.

Two significant developments occurred in 2004.

The one was the culmination of the process of the accession of the Republic of Cyprus to the European Union – a process began in July 1990 (when I happened to be the Permanent Secretary of the Cyprus Ministry of Foreign Affairs). It was recognized that Cyprus fully satisfied the requirements of membership and was admitted to membership even without a prior solution to the Cyprus problem.

The other was the rejection of the Annan Plan by the Greek Cypriots in a referendum by a vote of more than 76%. Much can be said about the Annan Plan (in fact, a plan by Alvaro de Soto and David Hannay) but time does not permit to go into it – perhaps during the Q and A period. What is relevant to our topic is that arbitration was a major factor, agreed reluctantly in February 2004 in New York by the two sides. The way arbitration was exercised by de Soto was to accept virtually all of Ankara’s demands, and this made inevitable the Plan’s rejection by the Greek Cypriots and thus the opportunity was lost. The Greek Cypriot rejection of the plan was definitely not a rejection of the solution but a rejection of the Plan as designed and presented by its creators.

This leads me to the present phase in light of the failure of the July talks in Switzerland, due primarily to the Turkish Government’s position on guarantees, rights of forcible intervention and indefinite presence of Turkish troops on the island. Several other issues (property, territory, EU law, the cost of a solution, etc) also remain outstanding. We shall see what the next steps will be in light of the just issued report of the Secretary-General and pending the Cyprus Presidential election in early 2018. President Anastasiades’ statement before the General Assembly on 21 September is a good document to take into account as to how things stand. In the past few days, Presidential candidate Nicholas Papadopoulos published his “new strategy” offering a different approach. The Secretary-General’s much awaited latest report (S/2017/814) was just submitted to the Security Council. He gives an account of what happened in the past two and a half years, expresses regret at missing the opportunity of reaching a solution in the July talks, but – and this is the relevant part of our topic of today – stresses that his good offices remain available “to assist the sides should they jointly decide to engage in such a process with the necessary political will, in order to conclude the strategic agreement that was emerging in Crans Montana”. We shall be hearing a lot about this Report in the next days and weeks.

In my view, the key continues to be Ankara’s position. Turkey aims at making Cyprus its protectorate. President Erdogan’s statements and actions (call it megalomania or wish to impose Pax Ottomana) do not augur well. His geopolitical ambitions for Turkey to be dominant in the region, and his islamist objectives in the region are evident and very discouraging. But the UN’s role in conflict resolution continues and so does UNFICYP’s role. As you may be aware, UNFICYP is currently subject to review – fifty three years after it was first set up for a period of three months!

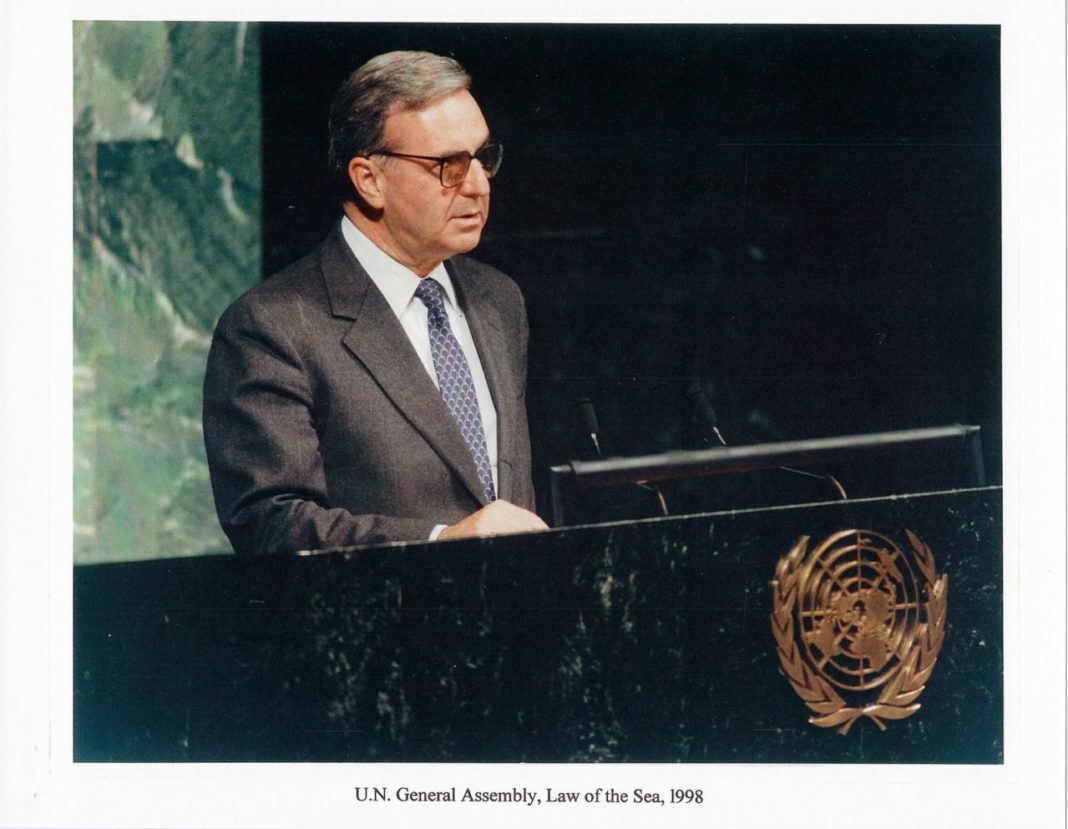

Before giving a chance for your questions, permit me to very briefly address a topic with which I have been familiar since the early 1970s, and this is the relevance and application of the Law of the Sea to Cyprus, an important topic in view of the hydrocarbons in the Eastern Mediterranean. The governing rules are set out in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOSIII) of 1982 (which I had the opportunity to negotiate and sign on behalf of Cyprus in Montego Bay in December of that year) and which has since acquired the force of customary law, having been ratified by the overwhelming majority of states in the world. The very concept of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) was created by the Conference and, partly as a result of our efforts and those of like-minded states, Article 121, on “Regime of Islands” provides that islands are fully entitled to the maritime zones of jurisdiction (territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf). On the basis of these rules, Cyprus proclaimed its EEZ and concluded EEZ delimitation agreements with three of its neighbors, namely Egypt (2003), Lebanon (2007) and Israel (2010) on the basis of the median line and with a provision for the settlement of disputes by arbitration. These are very important model agreements, which should definitely be preserved in any future settlement. Turkey, not a party to UNCLOS, has not only put forward claims for itself, encroaching on the EEZ rights of Cyprus, but also claims that the Turkish Cypriots have rights to these resources. The Cyprus Government has declared that any such resources are to benefit all citizens of Cyprus in any future settlement and has the support virtually of all states in its rights to its EEZ, with important international companies (TOTAL of France, ENI of Italy, ExxonMobil and Noble of the United States, among others) participating in exploration agreements. What is beyond doubt is that the EEZ resources of any state belong to the recognized Government of the state, and not to any ethnic or minority groups or communities within the state. If this were otherwise, why should not, for example, the Copts of Egypt, the Maronites in Lebanon, the Muslims in India and – why not – the Kurds in Turkey, not have the same rights? Turkey’s claims, recently reiterated by President Erdogan and other senior Turkish officials, ring alarm bells and this is another area where the UN’s role in conflict resolution, whether the Security Council, the General Assembly or the International Court of Justice, may have to be called into play.

Since I am speaking to a primarily American audience, allow me to depart by a way of a footnote, from our theme and address very briefly Cyprus – US relations and the US role on Cyprus developments – having served as Ambassador to the United States twice for fourteen years under four American Presidents). There is a tendency among some in Cyprus to, generally and uncritically, take a negative view of the United States. No doubt, there have been situations on which such criticism was well-founded. The George Ball and Dean Acheson activities in 1964 and certainly Henry Kissinger’s policies and “tiltings” in 1974 are such examples and of course Turkey, over the years, has been considered by US policymakers a major factor weighing heavily in their decisions. But it is often overlooked that there is also another side.

Back in 1962, President Kennedy invited President Makarios on a State Visit to Washington with full honors attaching to such visit. [It was then that the Archbishop asked me to draft his proposed major speech in Congress. When I, a green 25 year old junior diplomat, appeared overwhelmed by the magnitude of the task, he calmly reassured me: “Just put yourself in my position and write it as if you were Archbishop and President!”] There followed several other visits by successive Cypriot Presidents to the White House since then (in fact four, during my tenure), the last one being that of President Clerides in 1996.

In July 1964, it was President Lyndon Johnson’s letter to Premier Inonu that was instrumental in averting the then threatened Turkish invasion.

In 1967, it was Cyrus Vance’s dexterous diplomacy that defused the crisis over the Kophinou incident, and averted another threat of an invasion.

In 1972, the US averted an impending coup by the Greek Junta against Archbishop Makarios through the timely action of US Ambassador David Popper (this, of course, did not happen in 1974, under Kissinger, despite the timely warnings of the State Department’s Cyprus desk officer Thomas Boyatt).

In 1978, the US-British-Canadian Plan –in fact Matthew Nimitz’s plan-could have been, in my view – then and in retrospect – a sound opportunity for progress towards a solution and certainly would have secured the return of Famagusta even if no solution was achieved.

In November 1983, the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) of the so-called “TRNC” was strongly condemned both by Congress in joint resolution and by the Administration (including support for SC Res. 541 at the UN and a specially arranged visit by President Kyprianou to the White House to meet President Reagan) and the US was instrumental in averting recognition of this “legally invalid” entity by Islamic countries such as Bangladesh and still does.

In late October 1984, a letter by President Reagan to President Evren, elicited Turkey’s acceptance of “29+” on the territorial aspect and the non-insistence on rotating presidency – not enough for a breakthrough in the then ongoing Kyprianou-Denktash talks, but significant concessions nevertheless, as seen in perspective, certainly on the issue of the rotating presidency.

In 1995, Richard Holbrooke, as Assistant Secretary of State for Europe, was instrumental in securing the support of the US for the accession course of the Republic of Cyprus to the European Union, a strategic move towards the solution of the Cyprus problem through Greece, Cyprus and Turkey being (or becoming) EU members, on the parallel of the Northern Ireland situation.

In more recent years, Vice President Biden has tried to assist towards a Cyprus solution and, to some extent, so is currently Vice President Pence.

I will not even attempt to relate the numerous ways in which Congress, both the Senate and the House, supported the cause of Cyprus, other than to mention the congressionally imposed arms embargo on Turkey in 1975 on the “rule of law” issue, the financial aid to Cyprus over the years, being tripled every year by Congress over the Administration’s request, which went a long way towards alleviating the suffering caused by the invasion; major initiatives, such as the Pressler-Biden Amendment in 1984 in the wake of the illegal UDI; and the overwhelming support in Congress for the significant resolution in 1995 endorsing the Clerides proposal on the demilitarization of Cyprus.

Richard Haass, the current President of the Council on Foreign Relations and a Special State Department Cyprus Coordinator in the early 1980s, in a book entitled “Unending Problems” listed the Cyprus problem as one which needed to be managed since it could not be solved. So far he has proven right in this assessment. My own view is that the Cyprus problem is solvable, since the UN procedure is there, and the constitutional basis is agreed (as spelled out the Security Council resolution of 1994, earlier cited). What is missing is Turkey’s willingness to accept that reunited Cyprus should be a normal state (in the apt term used by S-G Guterres) free of foreign troops and settlers (at present there are more settlers than Turkish Cypriots in the occupied area), anachronistic foreign guarantees and rights of forcible intervention, which in any case are incompatible with peremptory norms of modern day international law. A functional state which can continue to play within the UN and the EU a constructive role in the region, as it has been successfully endeavoring to do in recent years despite its current limitations due to foreign occupation. A state economically flourishing through tourism, shipping and services and with the resources of its EEZ for the benefit of all Cypriots. It is an achievable objective, worth struggling for.

If a fair and functional solution is reached, every effort will be made to erase the memories of the recent past. Cyprus will maintain friendly relations and cooperate with all countries in the region, including, of course, Greece and Turkey, but also Israel and Egypt and other states in the region, on the basis of the principles of sovereign equality and good neighborliness. Cyprus has the economic and human potential as well as the geographical position to become a bridge of peace and understanding in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East region, as Switzerland and Austria are in Central Europe. It is very much our hope that this can become a reality for the benefit of all of the people of Cyprus and for peace and stability in the region.

Before concluding, let me summarize: The United Nations can and has played a considerable role in conflict resolution regarding the Cyprus situation. The Security Council, the General Assembly, as well as the Secretary-General have played and continue to play this role since the problem arose in late 1963 and even earlier, in the days before the independence of Cyprus. This role needs to continue, both in terms of peace making and of peace keeping. But the problem is solvable on the basis of the UN Charter and Resolutions, and the principles of the European Union, so that the reunited Republic of Cyprus will be a normal state, for the benefit of all its inhabitants, and for peace and stability in the region.

Thank you for your attention and I shall be glad to try to answer your questions.