“Our race was crucified many times, but here we are, still alive.” – General Theodore Kolokotronis.” 1

What did American statesmen say about the 1821 Greek Revolution? Americans were determined to stay out of European wars but were involved in political developments. Thomas Jefferson, the writer of the Declaration of Independence had a friendship with Adamantios Korais, a famous scholar and member of the Diaspora Greek movement.

In a Fall 1823 letter, Jefferson wrote to Korais “No people sympathize more feelingly than ours with the sufferings of your countrymen: but the fundamental principle of our government, never to entangle us with the broils of Europe, could restrain our generous youth from taking some part in this holy war. Possessing ourselves the combined blessings of liberty and order, we wish the same to other countries and to none more than yours which the first of civilized nations, presented examples of what man should be.” Jefferson did not grant Korais requests for public political support.”2

US President James Monroe in his annual 1822 address to Congress said, “a strong hope is entertained that the Greeks will recover their independence and assume their equal status among the nations of the earth.” A year later dec. 2, 1823, President Monroe announced the “Monroe Doctrine”, which excluded the United States from getting involved in European affairs and considered the then existing European governments as “de facto Legitimate.”3

On August 19, 1923, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams said, “If in the course of events, the Greeks should be enabled to establish and organize themselves as an independent nation, the United States will welcome diplomatic and commercial relations.”4

Daniel Webster’s speech in the House of Representatives in January 1824 said about the Greek Revolution that “the Greeks address the civilized world with a pathos not easy to be resisted. They invoke our favor…they stretch out their arms to the Christian communities of the earth, beseeching them, by a generous recollection of their ancestors, by the consideration of their desolated and ruined cities and villages, by their wives and children sold into accursed slavery, by their blood, which they seem willing to pour out like water, by the common faith and in the name which unites all Christians, that they would extend to them at least some token of compassionate regard.”5

Many statesmen showed support, but the US government did nothing. I was impressed with a speech by Henry Clay, the “Great Compromiser” that spells out in graphic terms the annihilation of Greeks. It is denied in March 2021 by the Turkish government. No international politician would use Clay’s words today.

This is the following speech Clay read to Congress that will be interesting to the modern reader. “Are we so humbled, so low, so debased, that we dare not express our sympathy for suffering Greece; that we dare not articulate our detestation of the brutal excesses of which she has been the bleeding victim, lest we might offend someone or more of their imperial and royal majesties? If gentlemen are afraid to act rashly on such a subject, suppose, Mr. Chairman, that we unite in a humble petition, addressed to their majesties, beseeching them, that of their gracious condescension, they would allow us to express our feelings and our sympathies. How shall it run? “We, the representatives of the free people of the United States of America, humbly approach the thrones of your imperial and royal majesties, and supplicate that, of your imperial and royal clemency—” I cannot go through the disgusting recital; my lips have not yet learned to pronounce the sycophantic language of a degraded slave! Are we so mean, so base, so despicable, that we may not attempt to express our horror, utter our indignation, at the most brutal and atrocious war that ever-stained earth or shocked high heaven? at the ferocious deeds of a savage and infuriated soldiery, stimulated and urged on by the clergy of fanatical and inimical religion, and rioting in all the excesses of blood and butchery, at the mere details of which the heart sickens and recoils?”

“If the great body of Christendom can look on calmly and coolly, whilst all this is perpetrated on a Christian people, in its own immediate vicinity, in its very presence, let us at least evince, that one of its remote extremities is susceptible of sensibility to Christian wrongs, and capable of sympathy for Christian sufferings; that in this remote quarter of the world, there are hearts not yet closed against compassion for human woes, that can pour out their indignant feelings at the oppression of a people endeared to us by every ancient recollection, and every modern tie. Sir, attempts have been made to alarm the committee, by the dangers to our commerce in the Mediterranean; and a wretched invoice of figs and opium has been spread before us to repress our sensibilities and to eradicate our humanity. Ah! sir, “what shall it profit a man if he gains the whole world and lose his own soul,” or what shall it avail a nation to save the whole of a miserable trade, and lose its liberties?”

Clay continues saying “But, sir, it is not for Greece alone that I desire to see this measure adopted. It will give to her but little support, and that purely of a moral kind. It is principally for America, for the credit and character of our common country, for our own unsullied name, that I hope to see it pass. Mr. Chairman, what appearance on the page of history would a record like this exhibit? “In the month of January, in the year of our Lord and Savior, 1824, while all European Christendom beheld, with cold and unfeeling indifference, the unexampled wrongs and inexpressible misery of Christian Greece, a proposition was made in the Congress of the United States, almost the sole, the last, the greatest depository of human hope and human freedom, the representatives of a gallant nation, containing a million of freemen ready to fly to arms, while the people of that nation were spontaneously expressing its deep-toned feeling, and the whole continent, by one simultaneous emotion, was rising, and solemnly and anxiously supplicating and invoking high heaven to spare and succor Greece, and to invigorate her arms in her glorious cause, whilst temples and senate-houses were alike resounding with one burst of generous and holy sympathy; in the year of our Lord and Savior, that Savior of Greece and of us; a proposition was offered in the American Congress to send a messenger to Greece, to inquire into her state and condition, with a kind expression of our good wishes and our sympathies—and it was rejected!” Go home, if you can; go home, if you dare, to your constituents, and tell them that you voted it down; meet, if you can, the appalling countenances of those who sent you here, and tell them that you shrank from the declaration of your own sentiments; that you cannot tell how, but that some unknown dread, some indescribable apprehension, some indefinable danger, drove you from your purpose; that the specters of cimiters, and crowns, and crescents, gleamed before you and alarmed you; and that you suppressed all the noble feelings prompted by religion, by liberty, by national independence, and by humanity. I cannot bring myself to believe that such will be the feeling of a majority of the committee. But, for myself, though every friend of the cause should desert it, and I be left to stand alone with the gentleman from Massachusetts (Daniel Webster), I will give to his resolution the poor sanction of my unqualified approbation.” It was rejected. United States government did not help the Greek revolutionaries gain their freedom. People, communities, and the Philhellenes of America helped financially and with volunteers.

References

Z 4. Zotos, Stephanos. “American Philhellenism and the Greek War of Independence”, Pilgrimage, March 1976, p.4.

- https://www.bartleby.com/400/prose/746.html

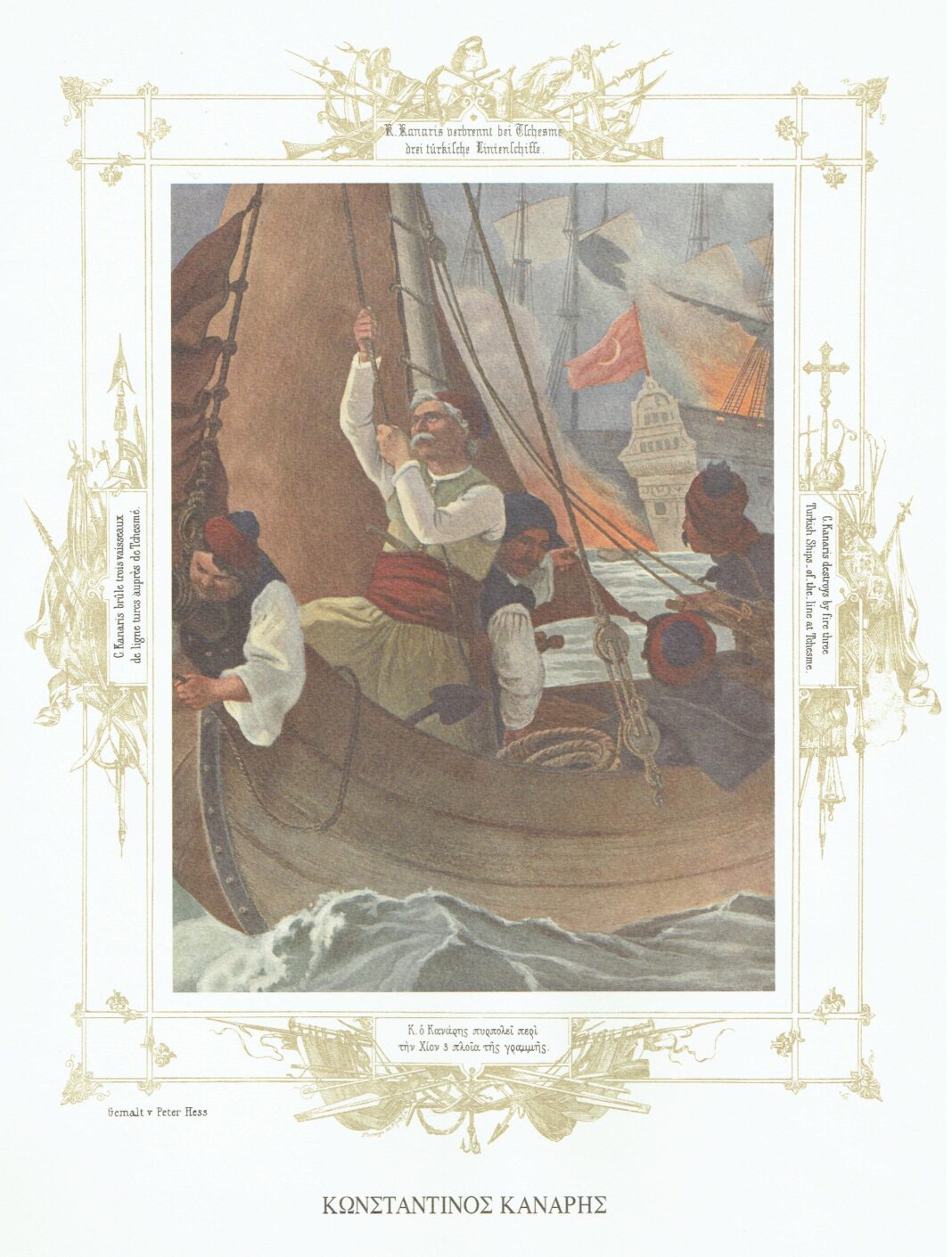

- .Peter Von Hess. 1821 Revolution of the Nation: 40 Lithographs, Delta, Athens, 1996.