“Hellenic Heads” Exhibition at the Embassy in Washington, D.C., and The Muses in Southampton, New York honors 6 important periods of Greek History over 2,500 years.

By Dorie Klissas

For George Petrides, a figurative sculptor based in New York City and Athens, the periods of Hellenic history that we can all relate to are the inspiration for a series of over-life-size sculptures of heads that are also personal and reflective. Hellenic Heads are on display at the Embassy of Greece in Washington, D.C. from May 4 to June 10, 2022, before traveling to The Muses, one of the pre-eminent cultural centers on Long Island, from June 16, 2022, through Labor Day. The Muses is affiliated with the Greek Orthodox Church of the Hamptons, the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, in Southampton, New York. Not only is this Church my family’s parish, but George and I met at Harvard in a course on 20th-century poet Constantine P. Cavafy. We have remained friends since that time.

It was my pleasure to interview George whose passion for history, life, and art is evident. Born in Athens, he was immersed in ancient Greek art and history from a young age and studied Greek and Latin at Harvard College. Combined with his sculpting skill, his work is personal, historical, raw, and legitimate. He believes that understanding the past is critical to understanding the present character of people. Influenced by the experiences of his Greek ancestors, as well as taking into account historical and family sources, his sculptures are a confluence of the past, present, and future.

For this interview, I caught up with George at the Consulate of Greece in New York on the occasion of his recent show, “Figure and Form: George Petrides and Nassos Daphnis” (December 2021 to February 2022). The two-artist show was curated by Paul Laster, who placed into dialogue the work of two New Yorkers, born in Greece fifty years apart. Paul Laster comments: “Taking a traditional approach to figurative sculpture, Petrides mines the past to create something new and when making his Pixel Fields / Aegean Series paintings, Daphnis tapped into new technology to update modernist abstraction. Petrides’ sculpted figures are perceptively born from the primordial mud of ancient cultures and modified in the artist’s hands, whereas Daphnis cleverly combined computer-generated graphics from an Atari ST with his own particular painting process.” The show was very successful, with strong attendance and publicity. Images of the work are on George’s website, www.petrides.art

Talking to George about his sculpture, and the people and history that influenced him, is like listening to a riveting mystery novel on tape. It makes you want to dive into your old history books because, finally, someone has put the story into context. As a result, you’ll find paragraphs on the historical periods George is influenced by which can serve as a “companion” to this interview.

Although George considers himself an artist from his childhood years, after college he entered the business world. A few years later, in his early 30s, the Muse summoned him to part-time art classes which he pursued for over 20 years, off and on, at such New York institutions as the New York Studio School on West 8th Street and the Arts Students League. Many times he thought about transitioning to making art full-time but didn’t “pull the trigger” until 2017 when the deaths of three friends and family within two weeks reminded him that our time on this earth is limited and precious. So in early 2018, he went to Paris to study art at the Academie de la Grande Chaumière, where distinguished students over the decades have included sculptors Giacometti, Bourgeois, Noguchi, and Calder. Upon his return to New York, he considered himself a full-time working artist. Since then he has shown his work in Athens, Dubai, London, New York, Monaco, and Mykonos.

What is the inspiration for your sculptures?

I have three inspirations: My daily life, ancient Greek sculpture, and what I call “Art Masterpieces” which includes photography, painting, literature. My daily life includes inspiration from people around me. I use them as models for my sculpture, people who mean a lot to me.

If you are Greek, you can’t help but be inspired by antiquity. There is nothing like going back to ancient times. For example, one of my sculptures, “Boxer at Rest (Self Portrait)” is inspired by a Hellenistic bronze statue at the National Museum of Rome called “The Boxer at Rest” which was loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013. When I saw the piece in New York, I was floored. In that moment I knew I needed to be a sculptor. It depicted a real person, a boxer who was beaten up, with cauliflower ears and open wounds in his skin. For my piece I started with a model, Raymond, posing in a similar way to the historic work to get some of the initial forms. After he left, I kept working on the piece, and I found that it acquired personal significance. I realized that I too, although not violent, was a boxer at rest–I had been through major illness, divorce, and a few other challenges. My version of the boxer, like the original, has suffered damage, but is very much alive, still curious, maybe with a wry smile, and able to go back into the ring. Wouldn’t that also describe many Greeks we know?

A lot of my work is like that, with multiple inspirations both historical and personal. I think people will see a lot of that in my newest show, Hellenic Heads.

And the art inspirations are not limited to ancient Greece. For example, when I was starting on my piece related to the Destruction of Smyrna, “The Catastrophe,” I was thinking about my grandmother and how she might have looked and felt in September 1922 when the city was burned and she lost her whole way of life. Call it serendipity; on my drive back from Monaco, where I had a solo exhibition, to Athens, I stopped in Florence for a few nights. There, at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, I saw two works that left me in awe: Donatello’s “Habbakuk” (1423-26) and Michelangelo’s “Deposition” (1547-1555). When you look at “The Catastrophe,” you may pick up on subtle references to both masterpieces.

What is your process?

I often start modeling by hand in natural clay in New York, looking at a live model or historical photographs. Next, the clay piece, still wet, is scanned in 3-D, becoming a digital file of millions of data points. This data is then manipulated in digital sculpting software, making alterations and enlarging it to up to three times lifesize. Then it might be sent electronically to Greece where it is 3D printed in plastic or CNC-milled in foam. I am happy to say that both these technologies are available in Greece. I work with one facility in Moschato and another in Ritsona, near Ancient Thebes.

When I have the enlarged sculpture back in the studio in Athens or in New York, I start on the piece anew, cutting with power tools, adding volume using materials commonly found on construction sites. Often the final form is cast in bronze, using the same lost-wax process that was used by the ancient Greeks 2,500 years ago. All of my castings to date have been done in Greece. Various patinas are applied to the final form in an expressionistic manner. From beginning to end, a piece can take a year and a half to make, from the first handful of clay to the piece ready for its exhibition.

Why did you decide to focus on sculpture?

In college, I took plenty of art history but no studio art, which is a pity because one of the significant sculptors of the 20th century, Dimitri Hadzi, also a Greek American, taught at our university the same years you and I were there.

So I didn’t take my first adult art class, an oil painting class, until I was in my early 30s, in 1996. I remember the first few pieces I worked on, and I recall the feeling of awkwardness. I was not a natural. Fortunately, I drifted toward drawing, which it turns out is the foundation of everything, including sculpture. Around 1998, I found myself at the New York Studio School in Greenwich Village, taking classes in the evenings and on weekend mornings. This went on for decades, part-time. At some point, in one of those random but meant-to-be occurrences, I wandered into a sculpture class and my hands worked with a mind of their own. I felt as the French sculptor Auguste Rodin said he felt when he first touched clay: That he was in Heaven.

In a larger context, sculpture is a Greek tradition. Oil painting is primarily what 20th-century European artists did, but sculpture is what our Greek ancestors did from Archaic times (7th century BC) into the Byzantine era, when colossal statues of Constantine the Great, the first Roman emperor to espouse Christianity, were placed throughout the empire.

Was there a turning point in terms of going full-time as an artist?

I attended art classes part-time for over twenty years while building my art history knowledge with frequent visits to museums, galleries, and lectures. Then came 2017. My beloved father died at age 88 after a protracted illness. About the same time, my friend Chris Gillespie, the jazz pianist at the Carlyle Hotel, died unexpectedly. He was younger than me. Then a few days after my father’s passing another friend was found dead at his weekend home–also my age, also unexpected. I got the message; it was time to do what I always wanted to do, to commit fully to making art. So I closed the doors to the business world and flew to Paris to study art in early 2018. I drew and painted every day from dawn to dusk. When I came back to NYC, I was committed.

How did the lockdown as a result of Covid affect your work?

Oddly, it was a productive period for me. I worked without interruption, often twelve hours a day, much of it in isolation. This deepened my commitment and my practice of making art daily. A side effect of the pandemic that I never could have foreseen was that people I didn’t know found me on the internet and started buying art without seeing it in person. It seems they were sitting at home and possibly redecorating. This too advanced my value as an artist. In the last two years, this has developed further. Now, some of my art I sell online to people I have never met, some to people I already know, some to visitors at in-person art shows.

Why focus on abstract sculpture rather than realist sculpture?

A lot of traditional sculpture, as well as contemporary sculpture, is what I would consider realistic. While realism takes a lot of skill, I find that less interesting because realism, like painting, has been affected by photography. Prior to photography, kings would commission portraits of themselves and disperse them amongst their many vassals. Everyone would say, “That is King Ludwig.” In the era of photography, that’s no longer an essential function of sculpture.

I find neo-expressionism very interesting (Neo-expressionism is a style of late modernist or early-postmodern painting and sculpture that emerged in the late 1970s). For example, German and American neo-expressionists Georg Baselitz and Marcus Lupertz: In their work, you see all these colors and textures. When I see their work, I am not thinking that someone looks like that, I am thinking the artists are trying to convey emotion.

There are many kinds of art, ranging from the cold, conceptual kind to the emotionally-driven work of Baselitz and Lupertz. I am happy to be closer to the latter end of that spectrum, for two reasons: First, it is who I am, and I believe in the saying, “Be yourself – everyone else is already taken.” Second, I think that abstraction and expressionism have real power. I hope you feel that power when you see the Hellenic Heads.

What is the inspiration behind your Hellenic Heads project?

I find my fellow human beings to be the most fascinating, difficult, and rewarding subject. Relationships are important to me in every aspect of my life, which is not to imply that I always succeed at them. I often experience an inability to understand or to connect, which probably drives my interest in figurative sculpting. As to the head specifically: It is the most human part of the human, the most expressive and the most difficult to convey and the most interesting when the conveyance succeeds. Every single one of my sculptures in this series is inspired not only by historical research but also by someone in my life. That’s what keeps it interesting for me.

The Hellenic Heads are a personal exploration of my Greek roots, through over-lifesized head sculptures that have been inspired by six important periods in Greek history. This series is a vehicle for, and the result of, my search for the Greek influences that have shaped me and the people closest to me, so I chose six periods in Greek history that could be deemed to have an ongoing influence on contemporary Greeks: the Classical Period, the Byzantine Period, the Greek War of Independence, the Destruction of Smyrna (of which the centennial is this year), the Nazi occupation and Greek Civil War, and finally, the Present.

Thalia, The Muse of Comedy

For “Thalia, the Muse of Comedy,” I was inspired by a famous classical statue by the same name in the Vatican. As I worked on the statue, which I wanted to be larger than life-size, it started taking on the features of my mother. I had photographs of my mother when she was nineteen years old in post-war Greece, 1949. At the time, Greece was in chaos, torn apart by poverty. So you see the individual’s anguish, juxtaposed with that familiar Classical style.

Archon

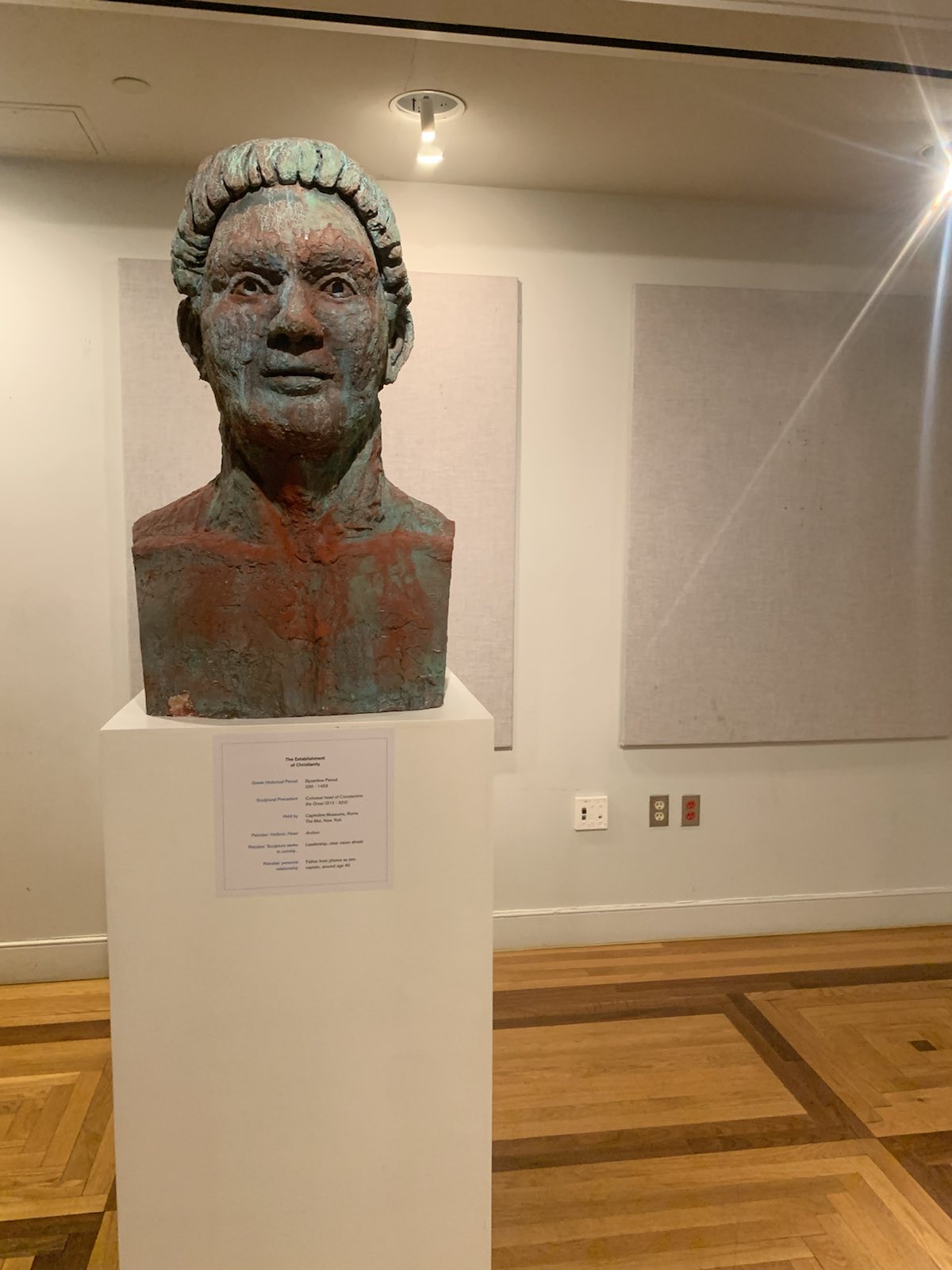

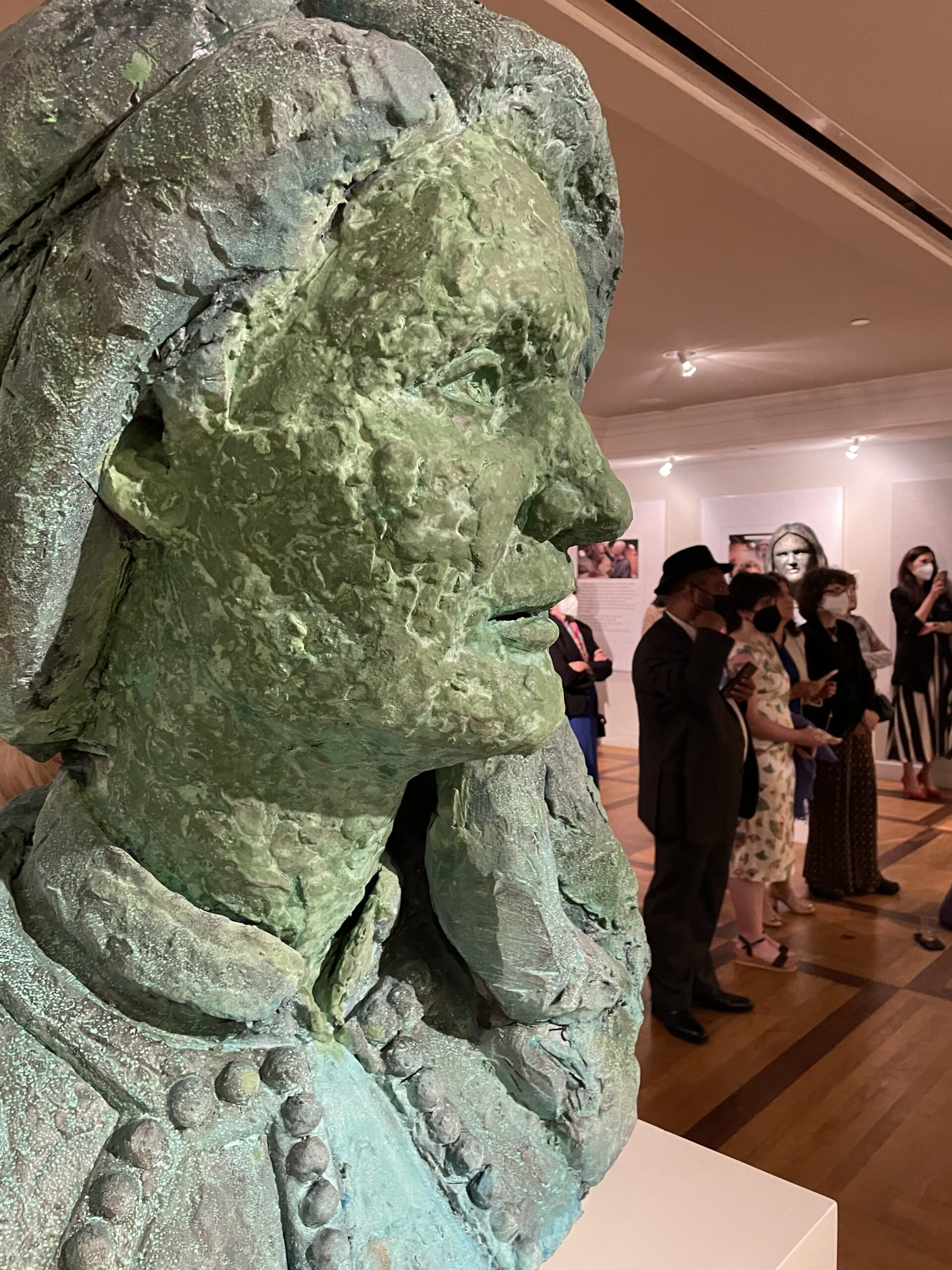

My father’s features are the inspiration for my Byzantine head. He was a sea captain, so there is a natural leadership role, so I likened him to the most famous of the Byzantine emperors, Constantine. There is a famous statue of Constantine, called the Colossus of Constantine, in Rome and another version at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was characteristic of the time for Constantine to have many statues of him propagated throughout the empire, as many as one hundred of them. My head is oversized and tries to convey my father.

Heroines of 1821

For the Greek Revolution, I am specifically interested in women of the era. For “Heroines of 1821,” I wanted to convey the strength, defiance and resilience of three female leaders in the War of Independence (Manto, Laskarina and the overlooked Domna Visvizi of Thrace), and found a modern Greek woman to sit for the piece, a woman with similar personality traits: My fiance!

The Catastrophe

My sculpture on the Burning of Smyrna in 1922 was inspired by my grandmother who has bloodlines going back to Smyrna. What was her life like? How did these experiences influence the person that I met? And then, what was my mother like? If you look at history, you are certain to get some insight.

In 1922, the Turks invaded Smyrna, burning the Greek and Armenian quarters which killed over 300,000 people. The rest were left waiting on the waterfront to be evacuated. Others were hanging on boats asking to be saved. Many of the Greeks living in Turkey were of a privileged class, and they went to Greece as fugitives, having lost everything. Studying the Destruction of Smyrna, including the experiences of my grandmother who survived it and the published diaries of her brother who fought in the war that preceded it, resulted in a sculpture conveying sadness of losing their homeland, but also dignity in accepting their fate and rebuilding their lives in a new country, Greece.

Life During Wartime

“Greek Man of the 1940s” is a study of a man going through the German Occupation of Greece and the Civil War. It’s also a self-portrait. To study Greece in the 1940s was to learn about my father’s time in an internment camp, to learn about the vibrant Sephardic Jewish community of Thessaloniki whose members were sent to Treblinka, to visit “Pigada” near Meligalas where a relative, the local doctor, was executed in what was the beginning of the Greek Civil War. Many of us are fortunate to have never directly had such experiences in our lives, but similar phenomena exist today, like in the daily lives of Ukrainians these past few months.

Ellinopoula

The last head is of my daughter. At age 12, she posed for “Ellinopoula Atenizontas to Mellon” which means Greek Girl Looking to the Future. In fact, she has grown so quickly, I am in the middle of capturing her once again. She is looking forward to the future with a slight smile. I hope this piece conveys the hope that a young girl may feel for her future and a country and a people may feel for theirs.

HISTORICAL PERIODS

Source: Catalog “Hellenic Heads”: George Petrides

——————————-

The Classical Period (510 BC to 323 BC)

As the birthplace of many of the pillars of Western civilization, Classical Greece is probably the period most familiar to history students of all levels. Its legacy, in the form of its politics, art, science, theater, literature, and philosophy, extended far beyond its time period and region to influence the culture of the Roman Empire, the European Renaissance, and the very foundations of modern civilization. Commonly the Classical Period is said to have ended with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, at which time the Hellenistic Period began.

The Byzantine period, or Byzantium, (330 to 1453)

The Byzantine Empire was the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The moment of its greatest extent and strength was in the early days of the empire, but it survived in some form until the fall of its capital city Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. Though its citizens referred to themselves as Romans, it was heavily influenced by Greek culture, and Greek (rather than Latin) was the official language.

The Greek Revolution against the Ottoman Empire (1821 to 1829)

The Greek War of Independence, known to 19th century Greeks simply as “the Struggle,” was a war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire. Greece had been under Ottoman control for close to four centuries, since the fall of Constantinople, and all previous attempts at independence were unsuccessful. The war led to the formation of modern Greece, and the victory is celebrated by Greeks around the world as Independence Day on March 25.

The Burning of Smyrna (1922)

The burning of Smyrna (current-day Izmir) came four days after the Turkish military captured the city, effectively ending the Greco-Turkish War. The fires raged for days in September 1922, largely destroying the center of art and commerce. As Smyrna burned, there was large-scale looting, rape, and killing, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands Armenians and Greeks. It also produced tens of thousands of refugees, many of whom fled to Greece to escape forced marches into Turkey. The survivors from Smyrna had a very difficult road ahead of them; people who had enjoyed life in a cosmopolitan city were suddenly displaced into extreme poverty and terrible conditions. Because of the scale of the tragedy, almost every contemporary Greek family has some historical connection to what many still call “The Catastrophe.”

The Nazi Occupation during World War II and the Greek Civil War (1940s)

The Nazis invaded Greece on April 6, 1941, and overran Greece within a month, despite British aid. Though liberated from the Nazis in 1944, a civil war soon erupted between the foreign-sponsored conservative government and leftist guerrillas. The government forces eventually prevailed, but the war left Greece in even greater economic distress than it had been following the end of the German occupation. With no control over the larger political maneuverings that rocked the nation, the life of the common person in 1940s Greece was typically one of extreme deprivation. The plundering of Greece by Axis powers resulted in mass starvation, often referred to as the Great Famine. An already-traumatized civilian population suffered thousands more deaths during the civil war due to violence, disease and starvation.

All photos are courtesy of George Petrides. Photo Credit: Guillaume Zicarelli.