By Dr. Robert Zaller, Drexel Distinguished University Professor of History Emeritus

Special to the Hellenic News of America

In the mid-twentieth century, Great Britain abandoned its control of a Mediterranean territory, leaving two ethnically and religiously divided populations, each with historic claims to its occupancy, to sort out competing claims of legal status and sovereign authority with little help from the international community. Unsurprisingly, intercommunal violence, the involvement of outside powers, and a de facto division of the two populations to the satisfaction of neither resulted. Decades later, the situation remains stalemated despite various attempts at adjudication, with lasting embitterment on both sides.

With that description, most people would think automatically of Jews and Palestinians on the contested territory between Israel and the Palestinian lands west of the Jordan River. But it applies equally well to a conflict the world all but ignores save for the principals involved themselves. That conflict, of course, divides the island of Cyprus, as it has for the past forty-seven years.

Cyprus is an island favored by nature in all respects but one: its proximity to the coast of Asia Minor or Anatolia, the large peninsula that juts out into the Black Sea, and the northern Mediterranean as the westernmost landmass of Asia. It has been ruled by Phoenicians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Ptolemaians, Romans, Byzantines, Frenchmen, Mameluks, Venetians, and, from 1571 to 1878, by the Ottoman Empire, which ceded it in the latter year to Great Britain. Among the many who contended for it were Richard the Lionheart and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick the Great. Shakespeare’s Othello is represented as a naval commander defending Cyprus on behalf of Venice. Itself a conqueror at times, it had once controlled Palestine and occupied Jerusalem. But the island was Hellenized during the period when Greek city-states flourished along Anatolia’s western shores and was recognized as a part of the Greek world during and the centuries that preceded the Roman conquest.

At various times, Cyprus was dominated by secular interests—it was for millennia a commercial mecca—but at times by religious ones as well. With the Ottomans, a Turkic element became part of the population mix, but the Ottomans ruled largely through local religious institutions, and thus, while Cyprus never lost its cosmopolitan character and Greek culture, its inhabitants were identified confessionally rather than ethnically. This, the millet system, served the Ottomans well for a long time. Different communities, locally self-governing, lived side by side in relative peace and good neighborhood.

Matters changed with the accession of British rule. From a marginalized outpost of a dying empire, Cyprus became a crucial link in a worldwide one then at its zenith. The substitution of the British for Ottoman rule was not merely a transfer of empires, but of one overarching ideology for another. Nineteenth-century Europe was embarked in general on a course of the empire among its leading powers—Britain, France, Russia, and a newly unified Germany—that would lead to its virtual control of the globe by 1900, but also to a competitive struggle between individual states based on the principle of nationalism.

Nationalism was not a new idea as such: since antiquity, human political development had taken three main forms: tribal, national, and imperial. Tribal association, the first and most primitive, had been primarily clan-based. Kingdoms, emerging from clan leadership, were territorially and dynastically based; the more ambitious of them, expanding through conquest, became empires. All early empires retained, to a greater or lesser degree, a core dominant group, and most of them signified the fact through a supreme ruler, the emperor, with the notable exceptions of fifth-century B.C.E. Athens and republican Rome. Power relations, however, were always subject to contest, with Cyprus, its own kingdoms emerging in the second millennium B.C.E., suffering periodic conquests from abroad as well as internally but occasionally extending itself imperially as well.

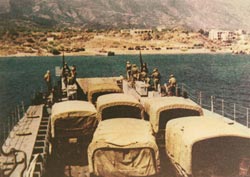

Turkish military ships at the coast of “Pente Mili” – July 20 1974.

Source http://karavas.eu/

Nation-states emerged gradually in Europe in the aftermath of the Roman Empire, but in the nineteenth century, the idea of ethnically rather than royally based states seized the Continent. To an extent, this was a regression to tribalism, with nations grouped around “peoples” and defined by shared language, culture, history, and, most importantly, imputed racial characteristics. This development coincided with the rise of European commercial dynamism and technological superiority, both of which created an impetus to expansion for reasons both of profit and prestige.

Modern Greece itself was a product of this process. The success of its revolution struck a blow at the now-decrepit Ottoman Empire, planting an ardent nationalism among the Greeks themselves that took the form of successive attempts to liberate Greek-speaking and Orthodox-worshipping peoples still under Ottoman control. This meant expansion on the European mainland where the Ottomans still ruled and on the island chains adjacent to it, to the south as far as Crete and east as far as Cyprus. The Greeks called this enosis, or union. It was Britain, however, navally as well as commercially dominant in the Mediterranean, that gained control of Cyprus.

The next phase of the story was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire during and immediately after World War I, and the emergence of what would become the modern Middle East. As an ally of the victorious wartime powers, Greece under Eleftherios Venizelos saw an opportunity to annex territories in Anatolia where sizable Greek populations still lived and were being subjected to genocide. Britain, using Greek forces as an entering wedge for itself, supported their incursion into Anatolia, but a Turkic resistance, aimed at creating a nation-state of its own, finally forced their withdrawal. This was the most critical, and in the long run the most calamitous moment in modern Greek history, a subject I have dealt with it in my preceding article, “The Genocidal Origins of Modern Turkey.” Here, I wish to deal with one aspect of it, the nature of the Turkish state that by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) emerged as the recognized ruler of Anatolia.

Ottoman rule had strongly discouraged nationalist consciousness and aspirations. In the detritus of its empire, only in Anatolia did an aggressive minority, the Turks, win power. Anatolia was home to many minorities, but only one, the Turks, had more than regional governing experience. To unite so a large territory, however, it had to be infused, forcibly as it turned out, with a national consciousness hitherto foreign in the Ottoman realms. This was largely the work of a tireless leader, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who saw in an ethnically-based secular nationalism the sole basis for a modern state.

Ataturk’s perception was not novel. When the Italian peninsula was unexpectedly unified in the 1850s, its founding figure, Camilo di Cavour, remarked that while he had created Italy, it remained to create Italians—that is, a single nation out of disparate elements. Ataturk had a far more difficult task. Italy possessed a common language and a long pedigree. Anatolia had neither, and, although the Ottoman sultanate had Turkic origins, its authority, now dissolved, could not be passed on. Ataturk, in short, had to create Turks in order to create Turkey, but with few materials available. He had to do it, moreover, in the midst of war and on the ruins of defeat. What he achieved was remarkable; the means by which he achieved it were appalling. Many modern states have been founded to the accompaniment of violence, civil war, and slaughter. Turkey is the only one founded on multiple and simultaneous campaigns of genocide.

Cyprus is, in part, a pendant to this story, and a modern extension of it. The Treaty of Lausanne recognized Ataturk’s regime as fully sovereign over Anatolia. Greek control over the Aegean islands was affirmed with the exception of two close to the Dardanelles Strait, Imbros and Tenedos, and the Dodecanese chain occupied by Italy. This arrangement, enforced by mandatory population transfers, satisfied neither side. For Greece, it meant the end of two and a half millennia of Hellenic settlement and culture in Asia Minor. For the new Turkey, it meant a cordon sanitaire against Turkish interest and development in the Aegean, even in islands close to its shores. Cyprus, tucked in against southeastern Anatolia, was a different case. Formally annexed as a British Crown colony in 1925, it belonged neither to Greece nor Turkey but to what was still the world’s largest empire.

The Lausanne Treaty guaranteed the majority Greek populations of Imbros and Tenedos full civil and property rights. These rights, unsurprisingly, were not honored; the Greek populations were driven out, and the islands fully Turkified. Turks pointed to a similar expulsion of Muslims from Crete in 1897, but, for the Greeks of Cyprus, the implications for them of what had happened on their sister islands could not have been clearer.

The Muslim inhabitants of Ottoman Cyprus had, as elsewhere, been counted for census purposes only by their religion; there were, technically, no “Turks” on the island, even after the establishment of Turkey itself. But the fervid Turkish nationalism espoused by the Ataturk regime necessarily affected this population, and Ataturk paid special attention to cultivating it. Greek Cypriot nationalists, alarmed by Ataturk’s aggressive posture, looked in turn to the mother country for their ultimate identity and security.

Cyprus played a critical role in denying fascism to the Middle East during World War II, and even today Britain retains important bases on its southern coasts. But Britain’s precipitous withdrawal from the region after the war, a part of its general dismantling of empire, put the future of the island in question. At the same time, Greece had realized its long objective of recovering the islands of the Dodecanese from a defeated Italy. All the islands of the Aegean were now in either Greek or Turkish hands. Cyprus was the only outlier.

Even in retreat, Britain still wished to keep control of Cyprus, as it did of Gibraltar, the two gates to the Mediterranean. Whether it could do so was, by the 1950s, in doubt. Greek nationalists with ties to the military formed a resistance movement, the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA). Its ultimate purpose was not independence for the island but enosis or union with Greece. But Cyprian independence was a first step to that objective, and so Britain was its first foe.

Enosis was not a new idea among Greek Cypriots, they have fought in hopes of achieving it as early as the Greek War of Independence. Nor were the British themselves wholly unsympathetic to the idea. The cession of Cyprus to Greece was endorsed by British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin at the end of World War II, but it had been rejected by Colonial diplomats anxious to preserve Britain’s interests in the Middle East and unwilling to antagonize Turkey, a major regional power.

Turkey had its own plans. Annexation was its goal, but that was politically inexpedient. Turkish Cypriots, as the Muslim population of Cyprus was now regarded to be, made up only 18% of the population. Greek Cypriots were four times more numerous, and almost entirely in charge both of the island’s economy and its patrimony. A mass deportation of them such as had occurred in Anatolia with the Treaty of Lausanne was unthinkable; so was a war between two states now yoked together as NATO allies, with a looming Russia at their borders. The furthest Turkey could go was to suggest a partitioned Cyprus with Greek and Turkish Cypriots separately governing themselves. But the latter, dispersed throughout the island, had no territorial base, and such a division would have required a Lausanne-type population transfer. As for Greece, it had now effectively become an American protectorate, and however Athens might dabble in the politics of enosis, no Greek government could openly advance such a plan—or the overthrow of British rule it would require. The most it could do was to arm EOKA surreptitiously, to which Turkey responded in kind, creating an armed force of its own, the Turkish Resistance Organization (TMT). In Turkey itself, there was already another organization, government- supported, whose name cast off any pretense at compromise: “Cyprus Is Turkish.”

To deal with the increasing polarization of the island, Britain convened a conference of Greek and Turkish representatives in August, 1955. Just as the conference was breaking up, with nothing settled, a government-sponsored pogrom struck what remained of the Greek quarter of Istanbul, killing relatively few but destroying thousands of homes and businesses. A final exodus of Greeks from Anatolia resulted. Greek and Turkish Cypriots now openly turned on each other in a low-level civil war marked by atrocities, chiefly although not exclusively on the Turkish side. Britain, finding its position now untenable, finally brokered a withdrawal from the island, retaining only two naval bases on the southern coast.

There was only one even temporary solution to the Cyprus problem at this point. By the London-Zurich Accords of 1960, an independent Republic of Cyprus was established, with an elected president who was to be Greek and a vice president who would be Turkish. Both officials would have veto power over legislation, and 30% of the seats in the Cypriot Parliament were reserved for Turkish representatives, nearly twice the proportion to Turks in the population. Meanwhile, the Turks had consolidated their numbers in towns and communities of their own. The Greeks did likewise, thereby embarking on a de facto partition of the island.

The new president, overwhelmingly elected, was the most prominent clerical and civic figure in Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios III. Makarios answered to no one as the head of an autocephalous, that is an independent Greek Cypriot church. Early in his career, he had been a co-founder of EOKA, and a passionate advocate of enosis. But his new position, and the political realities that had created it, forced him to abandon his earlier dream. He was now committed to an independent Cyprus in a power-sharing arrangement that would, hopefully, enable Greek and Turkish Cypriots to coexist.

It was not to be. Egged on by Ankara, now under military rule, Turkish Cypriots demanded ever-greater autonomy, while their Greek counterparts believed they already had too much. By 1963, the constitution established by the London-Zurich agreement had broken down, and, with increasing intercommunal violence, both Greek and Turkish military forces had landed on Cyprus along with U.N. peacekeepers. By 1964, Turkey was threatening its outright invasion and conquest, which was only by a stern warning from Washington. The U.S., however, had no interest in preserving an independent Cyprus. Its own plan, devised by former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, was to divide the island between Greece and Turkey, the bulk of it to be given Greece in a partial enosis with the remainder reserved as a Turkish canton protected by Turkey’s military forces. In this way, both Greece and Turkey were to get a slice of what they wanted, if not the whole. As so often in their past, Cypriots themselves were not to be consulted on their fate.

In 1967, Greece suffered its own military coup, and a seven-year descent into tyranny. Among its effects were revived intrigues against the Makarios government. Discussions were even held between the Greek Junta and Turkey a partition of Cyprus. At the same time, the Junta secretly sent the hardline EOKA leader Giorgios Grivas back to the island in contravention of a 1967 agreement with Ankara. Grivas’ role was to orchestrate the assassination of Makarios, who had already been the target of several attempts.

At this point, Makarios—supported by a Cypriot public that had overwhelmingly voted him a new term of office—was virtually the only figure on the world stage who wished to preserve the Republic of Cyprus as an established state and a member of the United Nations. Events moved swiftly to a climax when the Junta’s leader, Giorgios Papadopoulos, was overthrown late in 1973 by Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannides, who while still dealing with Makarios in 1964 had proposed settling the Cyprus problem by simply slaughtering Turkish Cypriots to the last man. Now, his plan was simpler: eliminating one man, Makarios, seizing his government, and effecting a settlement with Turkey on his own terms.

The attempt against Makarios, on July 15, 1974, was thwarted when he was rescued by British troops. Safe in London, he denounced the Junta for its coup and called upon the international community to reverse it. This was all Turkey needed to intervene in Cyprus under the terms of the Treaty of Guarantee, an annex to the London-Zurich accords which authorized Britain, Greece, or Turkey to unilaterally assure Cypriot independence, if necessary by force. It was under this agreement that Turkish forces landed in north Cyprus on July 20, seizing ports and a narrow strip for further penetration. Faced with this, Ioannidis’ coup collapsed, and with it the Junta in Greece itself. Makarios returned to resume his presidency, and former Greek Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis, an acceptable conservative figure and an opponent of enosis, flew home from exile to form a democratic government in Greece.

This solved none of Cyprus’ long-term problems, but it did provide an opportunity for renewed negotiation. Turkey, however, was resolved to impose its own solution, the maximum one available to it. On August 14-16, its intervention became an invasion when 40,000 Turkish troops landed on the island, swiftly occupying some 36% of its territory and driving 180,000 Greek residents south. Since the occupied territory was 80% Greek, this was ethnic cleansing pure and simple, the violent clearing of space for an illicit Turkish regime. This was followed within the year by a further “transfer” of population, with Greeks forced south of a U.N.-enforced ceasefire line and Turks brought north to replace them. The latter’s numbers would not suffice, however, and Turkey began a program that would bring 120,000 mainland Turks to permanently colonize its occupied territory. Within a week of the invasion, this was declared to be an autonomous Turkish administration, and in 1983 it was proclaimed the Turkish Republic of Cyprus.

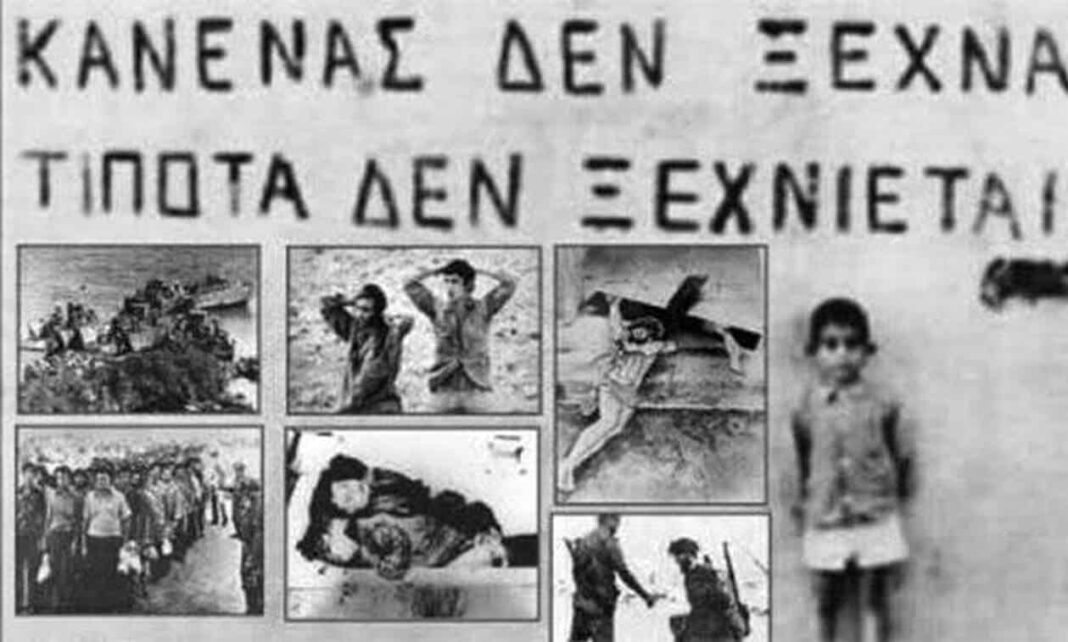

The United Nations denounced the occupation and subsequent colonization of northern Cyprus. No state in the world has recognized the so-called Turkish Republic in Cyprus except Turkey itself. In the violence that accompanied the Turkish invasion, some 8000 Greek and 1500 Turkish Cypriots were killed or remain unaccounted for. More than a third of the respective populations of Greek and Turkish Cypriots were and remain uprooted from their lives.

The events of July and August 1974 remain a subject of controversy; their results do not. The United States, preoccupied with the fall of the Nixon administration, did nothing to deter a Turkish occupation it clearly saw coming. Nixon himself had not only supported enosis but had been prepared to recognize the Ioannidis coup. It was his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, who on the eve of the Turkish invasion indicated he would do nothing to prevent or punish it. At the same time, he warned both the British and Greek governments against military interference of their own, to which they were legally entitled. In effect, Kissinger endorsed the Acheson partition plan of a decade before, and held the door open for Turkey to implement it on its own terms.

There matters stand today, after nearly half a century. The Turkish administration in northern Cyprus, a colony of Ankara, pretends to be a republic. The rest of the island is a truncated Republic of Cyprus, the state established in 1960 and continuing to claim the Turkish enclave torn from it. It does not declare itself what it is now almost wholly demographically, a Hellenic Republic, because that would mean accepting the Turkish occupation and the permanent loss of much of its cultural and material patrimony. It cannot unite with Greece, because that would mean war. It remains, in effect, a ward of the international community, whose peacekeepers patrol its Green Line and maintain a precarious peace. It exists, in short, at the sufferance of others.

The sporadic diplomatic efforts to reunite Cyprus over the past several decades have suggested a union under which its Greek and Turkish halves would be autonomous and self-governing under a nominal federal structure. The most ambitious of these plans, put forward in 1999-2004 by U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, may serve as a description for the rest. It would have created a so-called United Republic of Cyprus composed of the Turkish Cypriot enclave north of the Green Line and the present Republic of Cyprus south of it as “constituent” states, autonomous in their own affairs but linked by an elected president and vice president, with a bicameral legislature whose upper chamber would be evenly divided between Greek and Turkish Cypriot representatives and with a Supreme Court consisting of six Greek and three Turkish magistrates, but with three other judges from abroad as well. There would be a limited right of movement across the border for citizens of both states, and a limited right of return that would exclude hundreds of thousands of Greek Cypriots from any recovery of their former homes and property in the north. There would also be a right to station foreign troops on the island apart from U.N. peacekeepers, including a permanent body of Turkish forces. The plan was to be imposed unilaterally, subject only to approval by referendum. In short, the actually existing, independent Republic of Cyprus, a member of the United Nations and a candidate for admission to the European Union, was to be treated in exactly the same fashion as the occupying regime to the north, recognized only by Turkey and without international standing of any kind. The Republic was thus not to be a negotiating partner in its destiny, a maneuver described by one observer, Claire Palley, as the attempt “to pressure a small state effectively to accept the consequences of aggression by a large neighboring state allied to two powers, members of [the U.N.] Security Council” itself. The two powers were, of course, Britain and the United States, whose prior conduct had made the Turkish aggression of 1974 possible and were now, having accepted it for thirty years, seeking to make it permanent. They were backed by the European Union, whose own interest at this point—also prompted by the U.S.—was to admit Turkey as a member state. The U.N., and Annan himself, were mere tools. And the United Republic of Cyprus was to be the only sovereign state in the world permanently occupied by the foreign force that had divided it.

Turkish Cypriots, with everything to gain by this arrangement (except actual autonomy for themselves) approved the U.N. plan by a majority of 65%. Seventy-five percent of Greek Cypriots, with everything, including the protection of their own National Guard, to lose, rejected it. What followed was a chorus of denunciation directed against the Greek Cypriot vote, collectively by the European Union and individually by its member states and entities as far away as Bangladesh. The U.S. and Britain lifted their previous sanctions against trade and travel with northern Cyprus, in effect recognizing it as a state. Seldom if ever has the result of an internationally sponsored referendum by a supposedly free people been so categorically rejected.

The denunciations, however, were not unanimous. An academic based in Turkey himself, Eser Kakaras, declared that the entire purpose of the Annan Plan was the admission of Turkey to the European Union with “a pseudo-state [to be] used as a pawn.” Alfred de Zayas, a prominent scholar and U.N. official, said that it “weakened if not made ridiculous” every principle of international law adopted by the U.N. since its own founding. Numerous other experts spoke to the same effect across Europe and elsewhere. The farce fooled no objective observer. It did however unofficially legitimate Turkey’s occupation and continuing colonization and exploitation of northern Cyprus.

The development of what remains of the Republic of Cyprus continues to suffer from the division of the island that has deprived it of much of its land, resources, tourism, and cultural heritage, and left it a state substantially under illegal occupation. This has led to some unfortunate expedients, including the money laundering exposed by the 2008 world financial crisis and the much-criticized decision to offer citizenship to international investors. Other states of the European Union, including Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Malta, have provided tax havens and money laundering for powerful corporations and financial interests, but none under the pressures and abuse that Cyprus has endured for nearly five decades. This is not to excuse dubious or illicit conduct, but to suggest the costs to a nation given only the options of division or surrender. To this has now been added recent Turkish attempts to usurp Cypriot sea rights, as those of Greek islands in the Aegean.

The ultimate tragedy of Cyprus is that its mixed population had lived not in exclusionary zones but side by side in adjacent communities for centuries. Left to its own, it could have been a model of small nation prosperity. Instead, Cyprus has indeed become a “pawn” of others, as so often in its past. This makes the preservation and security of the truncated Republic of Cyprus all the more urgent a question for the world’s conscience.

Select Bibliography

Christopher Hitchens. Cyprus. Quartet Books. 1984.

William Hallinson and Bill Hallinson. Cyprus: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. 2005.

Claire Palley. An International Debacle: The UN Secretary-General’s Mission and Good Offices in Cyprus

1999-2004. Hart Publishing, 2006.