A hundred years! A hundred years are gone

Of Grecian mornings and of Grecian sunsets!

Make them a coffin wide, O carpenter,

And bury them, the hapless dead, in silence!

(Kostas Palamas 1859-1943)

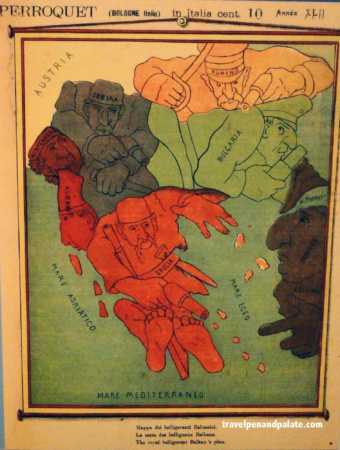

By the dawn of the 20th century the three major regional kingdoms bordering what would become the First World War’s Macedonian Front (Greece, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria) were players in a grand game of thrones. Britain, France and Germany would dictate the script. The chess pieces in this first round of what would be an ever more deadly 20th century spiral would be a generation of young men.

I have just crossed the Bulgarian border at Kulata into Greece traveling from the resort town of Bansko through the beautiful mountains of Pirin National Park into central Macedonia. Marketing guru and friend, Sofia Bournatzi, and her father, have greeted me. I’m told we’re on our way to Fort Roupel.

Although Fort Roupel was originally planned in 1914 it was not fully developed until the 1930s when the Metaxas Line of fortifications were constructed by Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas who had seized dictatorial control of the dysfunctional Greek government in 1936. Yet why was I being taken to a major World War II monument if my journalist assignment was to write about Greece during World War I, specifically the Macedonian Front 1917?

A tall, handsome, 22 year-old Greek army private, university educated in international relations and literature, speaking impeccable English, began an extended tour of the impressive site for this non-Greek speaking American journalist. It did not take me long to understand why I had been brought to Fort Roupel.

As our guide pointed out the geography surrounding Fort Roupel including the border crossing visible from this elevation that I’d crossed just an hour before, I realized I’m on the Macedonian Front. The tall, handsome, 22 year-old private was the same age as my uncle Leo d’Entremont – my father’s oldest brother known to me only through a photo – when fresh out of university in Canada he perished in the carnage of Ypres in 1915. I’m standing on the Macedonian Front where the “war to end all wars” was supposed to have made the Metaxas Line unnecessary and had just crossed the border where the forces of Germany and Bulgaria had invaded Greece in both wars.

Albert Einstein coined the famous saying that “those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it.” Yet in a conversation with a Serbian historian this summer in Belgrade at the Historical Museum of Serbia’s superb special exhibit on World War I, a new concept was proffered. History may not be a never ending circle but a spiral. It’s never repeated per se, but each succeeding event is contingent on the outcome of the preceding.

The heroic circumstances that make Fort Roupel a major memorial for World War II Greece will be the subject of another article. In 1916 this site was the catalyst for an all too different event.

The spiral of southern Balkan history, including Greece, for nearly a millennium preceding the 20th century revolved around two words – water and identity. In the 19th century an additional, powerful catalyst developed that would, quite literally, ignite a world conflict – oil.

It was all about water – circumventing the Dardanelles – for Bulgaria and Russia.

It was all about preservation of identity and culture – for Greece and the Ottoman Empire.

It was all about oil – direct access to the recently discovered reserves of the Arabian Peninsula – for the British, French and German Empires.

For millenniums the Balkans and Greece were fluid lands when it came to political identity. Geographically they lay at the crossroads of two continents, Asia and Europe, traversed by the legendary caravan and sea routes that stretched from China, India and the Near East to the Mediterranean Sea. From the 7th century BC through the 4th century AD, the region was the dynamo for the greatest expansion of culture, political thought, science and military conquests up to that point in recorded history. Successive empires – Persia, Macedonia and Rome – left a legacy that became a foundation for the next 1,700 years.

Persia’s failure to extend its empire into Europe gave the Greek states Asian ambitions. Alexander the Great’s successful empire building for all practical purposes created Greece as a political entity. The Romans carved their empire into geographic units that roughly gave definition to the amorphous Balkans. By the 4th century AD the world was ready for another dramatic twist in the spiral.

A weakening Western Roman Empire was plagued by internal corruption exacerbated by incursions of nomadic ethnic groups from both north and east. In the Balkans Indo-European people such as the Croats and Bulgars intermixed with the already multi-cultural “fruit salad” – as Mussolini described the region in the 1920s – that Greek and Roman domination had created. Yet it was Roman Emperor Constantine that fortified and energized the east by moving the empire’s primary capital to his new city on the Dardanelles, Constantinople, in the 4th century.

Besides cementing the primacy of Christianity within the empire, Constantine’s action created a new hybrid of Hellenic/Near Eastern civilization in the succeeding Byzantine Empire for the next thousand years. Yet this hardly brought stability to the Balkans – the rise of Islam (7th century), the Great Schism between the Roman and Orthodox Christian churches (11th century), the ill-fated Crusades (11th – 13th centuries), the fall of the empire and Ottoman conquest (15th century).

From the 15th through the 18th centuries the Ottoman Empire brought a degree of stability through their inclusive philosophy of governance. Diversity was tolerated in ethnic and religious expression as long as direct challenge to the primacy of the State and Islam was not voiced. For certain groups, such as the Jewish diaspora, it was a golden age that created the platform for a cultural renaissance.

Yet it was in the fin de siècle of the 18th century that Enlightenment theory – Hellenic humanism revived – morphed into 19th century concepts of nationalism that destabilized once more the Eastern Mediterranean world. The Ottoman Empire faced corruption, discord within its vast territories and the expansionist dreams of the Hapsburg’s Austria. By the 1870s a series of wars and rebellions against the Ottoman’s recreated the “fruit salad” of Balkan kingdoms, including southern Greece (1820s), yet with ever shifting borders.

No sooner did the new kingdoms emerge then they were at each other’s throats over nebulous territorial claims. For sure the kingdoms all had objectives. Bulgaria lusted over Macedonia and eastern Thrace. Despite Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast it had no direct access to the Mediterranean since the Ottoman Empire controlled the Dardanelles. Greece was a kingdom barely half the size of its pre-Roman days. The Ottoman Empire desperately wanted to hold onto what was left of its European provinces – Epirus, Macedonia and Eastern Thrace. Bulgaria was adamant that it would fulfill its dream of access to the Mediterranean through the conquest of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace.

The First and Second Balkan Wars (1912-1913) in the larger scenario were mere dress rehearsals for the Great War. For a brief period in 1912 when Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro and Greece united to form the Balkan League and take back Epirus, Macedonia and Eastern Thrace from the Ottomans it seemed a new dawn of cooperation. Yet what became a virtual deathblow to the “sick man of Europe” belied the underhanded promises of the European powers that controlled the script.

Unknown to Greece, Bulgaria had been promised by Britain and France that it would receive the cherished objectives it so longed – access to the Mediterranean, Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. Yet when the treaty was signed in May 1913 these lands were reunited with the Greek kingdom for the first time in over 400 years. Within less than a month, Bulgaria turned on its recent ally.

The Second Balkan War ended very quickly at the Battle of Kilkis on the Hill of Heroes, 19 – 21 June 1913. The hill overlooks Kilkis and was strategic to taking the city with the objective to then capture Serres with a clear road to Thessaloniki. Both sides lost in excess of 4,000 dead. I climbed this steep compact hill. The carnage must have been horrendous.

It was a surprise attack by the Bulgarians who first took this very steep hill. Four thousand dead later, the Greeks succeeded in pushing the Bulgarians off the hill. The battle was over, but not war.

Most readers know the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne in Sarajevo, Bosnia, in 1914 was the spark that ignited the First World War. Austria blamed the Kingdom of Serbia and the rest is the history of the most despicable war of modern times.

I was in Sarajevo in July. It hardly remembers its seminal place in this great conflict being still traumatized by its more recent horrendous experience in the 1992-1995 Yugoslav Civil War – its spiral.

Bulgaria joined the Central Powers – Germany, Austria and the Ottoman Empire – in 1915 after once more being promised their elusive access to the sea. The Entente – Britain, France and Russia – promised a quick end to the Ottoman Empire and aid to Serbia, yet could deliver on neither after the disaster of Gallipoli and Bulgaria’s conquest of Serbia in 1915. In an epic retreat, the remnants of Serbia’s army, government, and thousands of civilians, made it though the Albanian mountains as winter closed in to protection on the Ionian island of Corfu.

Eventually by 1916, through the insistence of France, forces from the Entente flooded into Thessaloniki, second largest city in Greece and the most strategic port of Macedonia. Bolstered by the revived remnants of the Serbian army, Thessaloniki became a fortified camp and the staging ground against a Bulgarian advance. The allied forces created the Macedonian Front, a 480 km line from Albania to Eastern Thrace.

But where was the Greek army?

Eleftherios Venizelos (1864 – 1936) Prime Minister of Greece strongly favored Greek entry into World War I on the side of the Entente. He felt that Great Britain would expand its influence in the Middle East regardless of the outcome of the war. Yet King Constantine I and the Army General Staff were opposed and kept Greece officially neutral. Why? … has been the topic of debate to the present day.

It may have had to do with family. It’s confusing enough that the Greek Royal family since the 1830s was of Danish descent, related inevitably to Queen Victoria therefore most of Europe’s royal houses, but his wife, Queen Sofia, was the sister of Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II.

It may equally have had to do with the mysterious assassination of his father, the revered King George I, who after 50 years on the throne was gunned down in Thessaloniki shortly after its liberation from the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War and before news of the secret territorial promises made to Bulgaria. Constantine may simply have distrusted the Entente.

The conflict between the two came to a head in August 1916. Bulgaria launched a strong offensive against the allies in the eastern and western part of the Macedonian Front gaining limited success. Their success was helped by King Constantine’s order that the Greek army not participate.

Fierce fighting occurred between the Bulgarians and Serbs on the central Front, but allied forces pushed initial Bulgarian advances back during the drawn out bloody battle in the mountainous terrain of Kazmakchalan, resulting in combined losses of over 200,000 dead or wounded on both sides. Yet by mid November 1916 parts of southern Serbia had been liberated from Bulgarian occupation.

The resulting conflict between the two political leaders led to what’s known as the National Schism – a political split between Parliament and the Monarchy that continued much to the Kingdom’s disadvantage for decades. On the 26 September 1916 with the support of many Greek officers in Macedonia Venizelos declared a “revolutionary government” in Thessaloniki and placed the Greek army under its control. The monarchy was sidelined.

By June 1917 King Constantine was forced to abdicate the throne and departed in exile with Queen Sofia and the Crown Prince. Prince Alexander, a younger son, assumed the throne. Parliament under Eleftherios Venizelos declared war on the Central Powers.

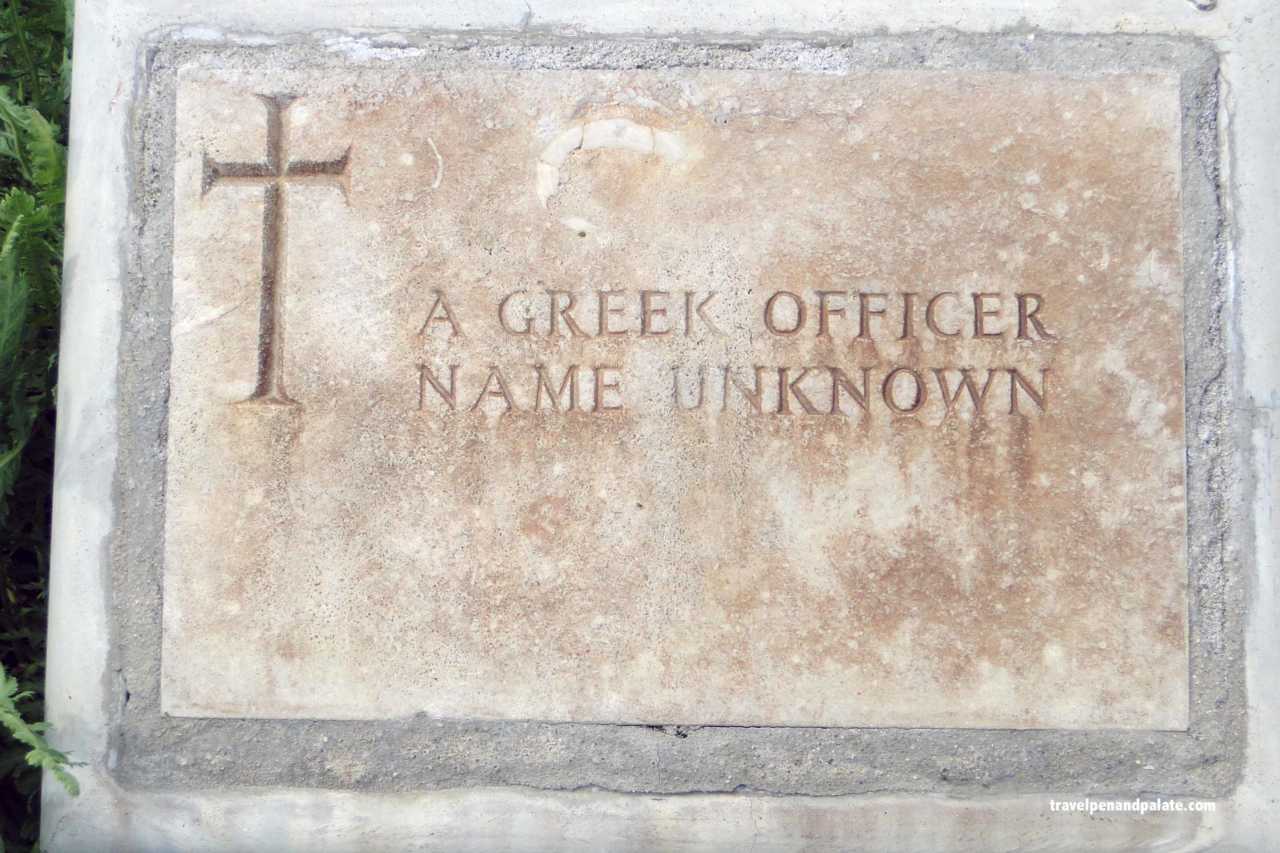

At the first battle at Lake Dorian, 1917, on the eastern flank of the Macedonian Front, an attempted Bulgarian offensive was stopped. As 1917 drew to a close Greece was in political turmoil, the Western Front was at a stalemate, but the Macedonian Front had held. Yet the cemeteries, the marble fields of Greece, were expanding with ever increasing numbers of Greek, British, Serbian and French dead young men – a lost generation.

Special Thanks: Thessaloniki Tourism Organization, the Municipalities of Serres and Kilkis, and Sofia Bournatzi of PASS PARTOUT Tourism Marketing, DMC for their sponsorship and assistance in preparation of this article.

Pass Partout, Thessaloniki and Kilkis have made an impressive video summarizing key events along the Macedonian Front: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8L8ELTKTAyk

Travel with Pen and Palate to Greece and the world every month in the Hellenic News of America